Nation's Notebook

NATION FAMILY CHRONICLES

Book I - THE NATIONS

Chapter 3

The Colonials

The Nations Move South

1

Growing a Family in New Jersey

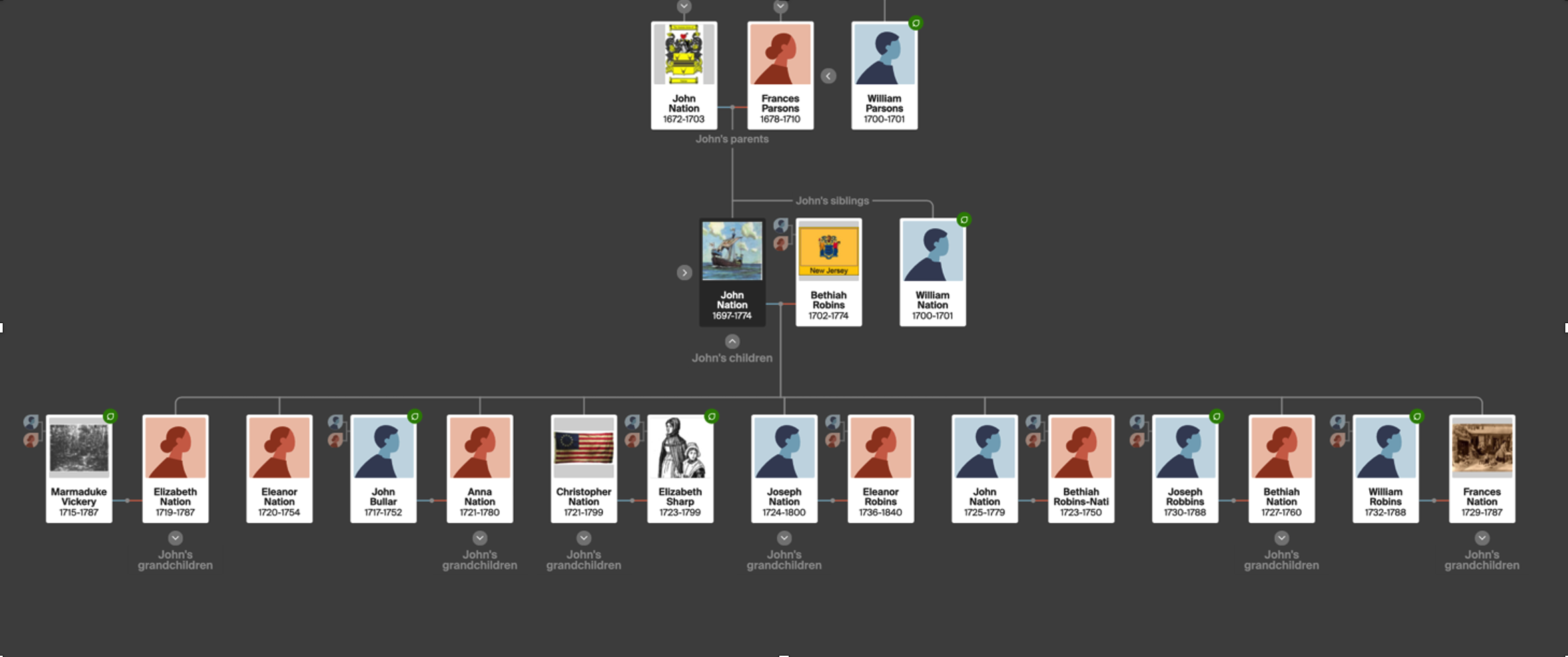

John Nation, 21, took Bethiah Robins, 16, to be his wife sometime in 1718 in a Quaker wedding. Their Puritan Protestant neighbors would have thought their marriage scandalous because it proceeded without benefit of clergy or even the utterance of vows because the Quakers authorized no clergy, did not take oaths, and did not stand over a couple to marry them. Believing marriage to be an act of God and not of man, the couple to be wed stood before God in the presence of witnesses and made “declarations” to one another. The custom of the Society of Friends was to record the declaration in a register, but unless that particular register should become available we do not have a record of the date of John and Bethiah's marriage.

A good deal of circumstantial evidence indicates their association with the Society of Friends. Bethiah, of course, had been raised as a Quaker. John Nation apparently had a positive upbringing in service to a benevolent Quaker family. There are many aspects of Quaker spirituality and ethics he must have found appealing, including a culture of equality not only between classes but also between the sexes. They found guidance through an “inner light,” combined (perhaps paradoxically) with biblical literalism. Their radical rejection of religious formalism along with their conscientious pacificism and their refusal to take oaths magnified the differences that made them stand apart from the rest of their society. Yet truly, the Quakers were no different from the Puritans or the Presbyterians in what they had come to the New World to seek: a better, freer way of life.

The newlyweds established residence in Freehold Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. The colony was, by the second decade of the 18th century, a burgeoning agricultural enterprise still much in need of commercial development. In report in 1721, royal economists for King George I describe the colony thus:

This province produces all sorts of grain or corn, the inhabitants likewise breed all sorts of Cattle, in great quantities, with which they supply the Merchants of New York and Philadelphia, to carry on their trade, to all the American Islands; but were they a distinct Government, (having very good harbours) merchants would be encouraged to settle amongst them, and they might become a considerable trading people; whereas, at present, they have few or no ships, but coasting vessels, and they are supplied from New York and Philadelphia with English Manufactures having none of their own.1

John at last came to the end of his term of servitude as a laborer on the Beaks farm. His freedom dues were 2 suits of clothes, 7 bushels of corn, 2 hoes and an axe.2 He apparently built a house for himself and his bride and continued to farm, and while it seems he acquired some property there is no record of these transactions.

That, at least, appears to me the most likely scenario in view of the facts we know. We have documentary evidence of young John Nation as an indentured servant in New Jersey. There is an apocryphal story that John was kidnapped and sold into slavery. This is possible but such kidnapping was rare, there is no specific evidence for it, and it simply does not fit with other facts, chiefly that his mother and great grandmother also came to New Jersey around the same time. Their transit is not documented, but Nation family genealogists are unanimous that both of the women died in the colonies and not in North Petherton.1 It is hard to imagine how these two poor widows would find a way to make the expensive voyage without some leverage.

He seems to have had his house lot assigned to him on Chestnut Brook, where he undoubtedly lived because he was assessed for taxes on 20 acres in Upper Freehold Twp, Monmouth Co., New Jersey on 1 Apr 1731 to rebuild "the Court House built in 1715 having been destroyed by fire in December 1727."3

Did he continue in the Beaks' employ after gaining his freedom? If so, it was probably not for long. Did he instead start working for his brothers-in-law who had inherited several hundred acres from their grandfather Daniel Robins? It seems likely.

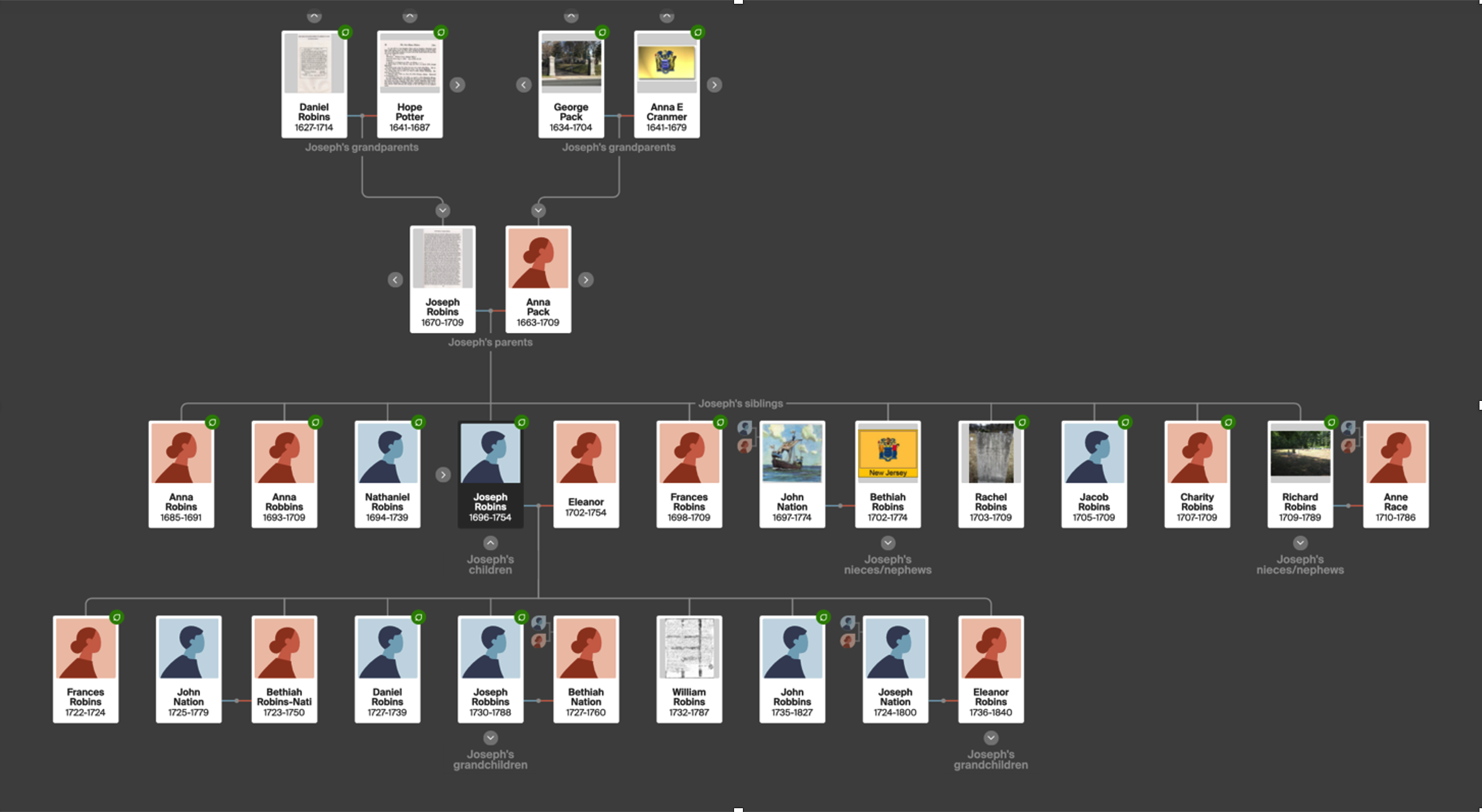

The newlywed couple established strong ties with Bethiah's siblings, especially with Joseph Robins, a man very near in age to John Nation. Joseph was the third born, the second son, and the namesake of his father who had inherited a substantial portion of Daniel Robins's 500 acre legacy.4 According to his will, the elder Joseph had acquired other property as well and, facing an untimely demise by illness, divided it between his sons Nathaniel and Joseph, Jr.

Bethia's brother Jacob Robins was listed for 250 …. Nathaniel was listed with 120 acres…. Daniel Robins (b.1692) & wife Elizabeth sold 2 tracts of land to William Hutchison. The Deed dated 20 Jun 1748 mentions as boundaries"...to a walnut tree marked on four sides, it being a corner of John Nation's land and agreed to by Jacob Robins and Nathaniel to be the corner between them..." Shortly afterward on 12 Dec 1748 Jacob Robins quit claims to Henry Chamberlin for a … meadow which was conveyed to him by Christopher Nation by a conveyance, dated 10 Dec 1748, "from which sd. Nation had Right to the land from his father, John Nation, by a Power of Attorney."5

Coming of age near the time of his sister's marriage to John Nation, the younger Joseph doubtless would welcome help to work the family farm that the England-born, former servant boy could give.

In the meantime, John and Bethiah began right away to build a family. Bethiah got pregnant soon after their wedding and their first daughter Elizabeth arrived the following year. Over the next ten years they would have seven more. Eleanor was born to them in 1720. The following year they welcomed twins, Anna and Christopher. After a respite from childbearing, Bethiah delivered Joseph (named after her brother) in 1724. And then in 1725 came John Jr., the fifth John Nation in consecutive generations, born 100 years after his second-great grandfather. The daughter born in 1727 was called Bethiah after her mother, and the girl born in 1729 was named Frances in memory of her father's mother.

In 1720, the same year of the birth of Eleanor Nation, 24-year-old Joseph Robins married an 18 year-old coincidentally also named Eleanor (or Elenor).6

While John and Bethiah were expanding their family, Joseph and Eleanor followed suit. Between 1722 and 1724 Eleanor gave birth to three girls who were given the significant family names Frances, Bethiah, and Eleanor. Following a break of a couple of years, the childbearing began again with a round of boys given similarly significant names: Daniel (1727), Joseph (1730), and William (1732). All these Robins children were born in Monmouth County, New Jersey.

1 “The Economies of the 1720s,” cited in https://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/colonies1720.htm. Spelling peculiarities preserved; italics for emphasis mine.

2 “John Nation,” author unknown.

3 “Stepping Forward to 1840,” Nation Study. www.NationStudy.com/histories/step.php

4 As shown in the chart of Land owned by Joseph, Nathaniel & Moses Robins, published in Robins, Robbins of New Jersey, 208.

5 “Stepping Forward,” op. cit.

6 We are not certain of her last name or her family. Many family genealogies call her “Eleanor Nation” and identify her as John Nation's sister,. They are surely mistaken about that. There is no evidence that John Nation had a sister and good circumstantial evidence to the contrary. Eleanor's birthdate and place are said to be 1702 in Monmouth, New Jersey, but that was a year before John Nation's father (John III) died in North Petherton, Somerset, England, and at least a few years (closer to 5) before the child John journeyed with his mother to the New World. But could the New Jersey ascription be mistaken, and she have been born in North Petherton? Some confidently maintain that she was. If she was born in 1702 it is materially possible for her to be John's sister by his father and mother, but there is no record of her birth and baptism on the church rolls—although there is such a record for John and his short-lived brother William. In short, there is no evidence that John Nation had a sister at all. Where then did the idea come from that Mrs. Eleanor Robins was John's sister? It appears to be the reference in Joseph Robins's will appointing his “brother-in-law John Nation” to serve along with Eleanor his wife as executor. Indeed, they were brothers-in-law: John Nation had married Joseph Robins's sister, not the other way around.

2

New Opportunities in Virginia

In the early 1730s, both John Nation and Joseph Robins decided that they had outgrown their fortunes in New Jersey and should move south together. Why? A historian observes, “Most migrants moved because of economic reasons; the perceived opportunity of acquiring more land and building better lives was central to the decision-making process.”1

The prospect of owning a significant tract of farmland would understandably draw John to make such a dramatic change. Joseph also apparently saw an enlarged opportunity in the South that made him want to leave behind his inheritance in New Jersey, possibly selling it to his brother Nathaniel.2 We can only guess which of the brothers-in-law took the initiative, but that they took it together is a documented fact.

Their target destination was the Virginia backcountry, a fertile but wild area later known as the Shenandoah Valley. The Nation and Robins families joined the earliest settlers of that area.

Initial settlement into the Valley began in 1732 with families from Pennsylvania and New Jersey, including Quakers Alexander Ross, Morgan Bryan, and Jost Hite, moving into the area. In the spring of 1732, Hite, his sons-in-law George Bowman, Jacob Chrisman and Paul Froman, along with 16 German and Scotch-Irish families, began to move into the Valley along Opequon Creek.3

The Nation and Robins families possibly accompanied the group led by Alexander Ross.4 By 1733 they had departed New Jersey for the Virginia backcountry. John and Bethiah Nation came with their seven children. Elizabeth, the oldest, was about 14; young Frances was not older than 4; and Christopher, the oldest boy, was 12. Joseph and Eleanor Robins brought their six children which included babe-in-arms William.

1 Creston S. Long III, “Southern Routes: Family Migration and the Eighteenth-Century Southern Backcountry.” PhD Dissertation, College of William and Mary, 2002.

2 However, both John and Joseph evidently continued to hold title to at least some New Jersey properties long after moving to Virginia. According to Nation Study: Stepping Forward to 1840 in America, https://nationstudy.com/histories/step.php

Bethia's brother Jacob Robins was listed for 250 …. Nathaniel was listed with 120 acres…. Daniel Robins (b.1692) & wife Elizabeth sold 2 tracts of land to William Hutchison. The Deed dated 20 Jun 1748 mentions as boundaries"...to a walnut tree marked on four sides, it being a corner of John Nation's land and agreed to by Jacob Robins and Nathaniel to be the corner between them..." Shortly afterward on 12 Dec 1748 Jacob Robins quit claims to Henry Chamberlin for a … meadow which was conveyed to him by Christopher Nation by a conveyance, dated 10 Dec 1748, "from which sd. Nation had Right to the land from his father, John Nation, by a Power of Attorney."

3 Ann Schaefer Persson, “The Archaeology of Opequon Creek: Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in the Material Culture of an Eighteenth-Century Immigrant Community, Frederick County, Virginia” (W&M ScholarWorks, 2004), 18.

4 See the list by J. Michael Frost, “The Founders of Frederick County, Virginia and the Quaker Hopewell MM in 1734/1735.” The Nation and Robins (or Robbins) names do not appear in this list, but as Frost admits that the list is incomplete and names only patent holders as of a certain date. His source is Kerns, Wilmer L., Frederick County, Virginia: Settlement and Some Frist Families of Back Creek Valley -- 1730-1830, Baltimore, MD: Gateway Press, Inc., 1995, pp. 561-564.

3

The Nature of the Journey

Crestin S. Long describes what it was like to make this migration. The first step was planning the journey and packing belongings.

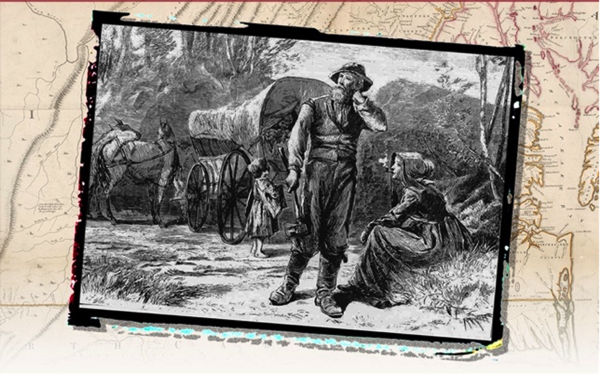

Little has survived in the way of direct evidence from migrants to indicate what exactly this process entailed. There is no extant checklist of items that migrants brought along with them. Most probably packed what they could from their own households or, in the case of landless migrants, their personal belongings onto wagons, horses or other pack animals and set off on one of the many roads to the southwest.1

One of the most important preparations was to secure a suitable vehicle to move a large family. They would certainly need a wagon, of which there were several varieties available. During this period the Conestoga wagon, built in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, rose to prominence. Longer and heavier than earlier designs and with an upcurved bed, it was better adapted to traversing rugged terrain. However, its size and weight required at least a four-horse team, and the two families would have to make do with whatever was available to them.2

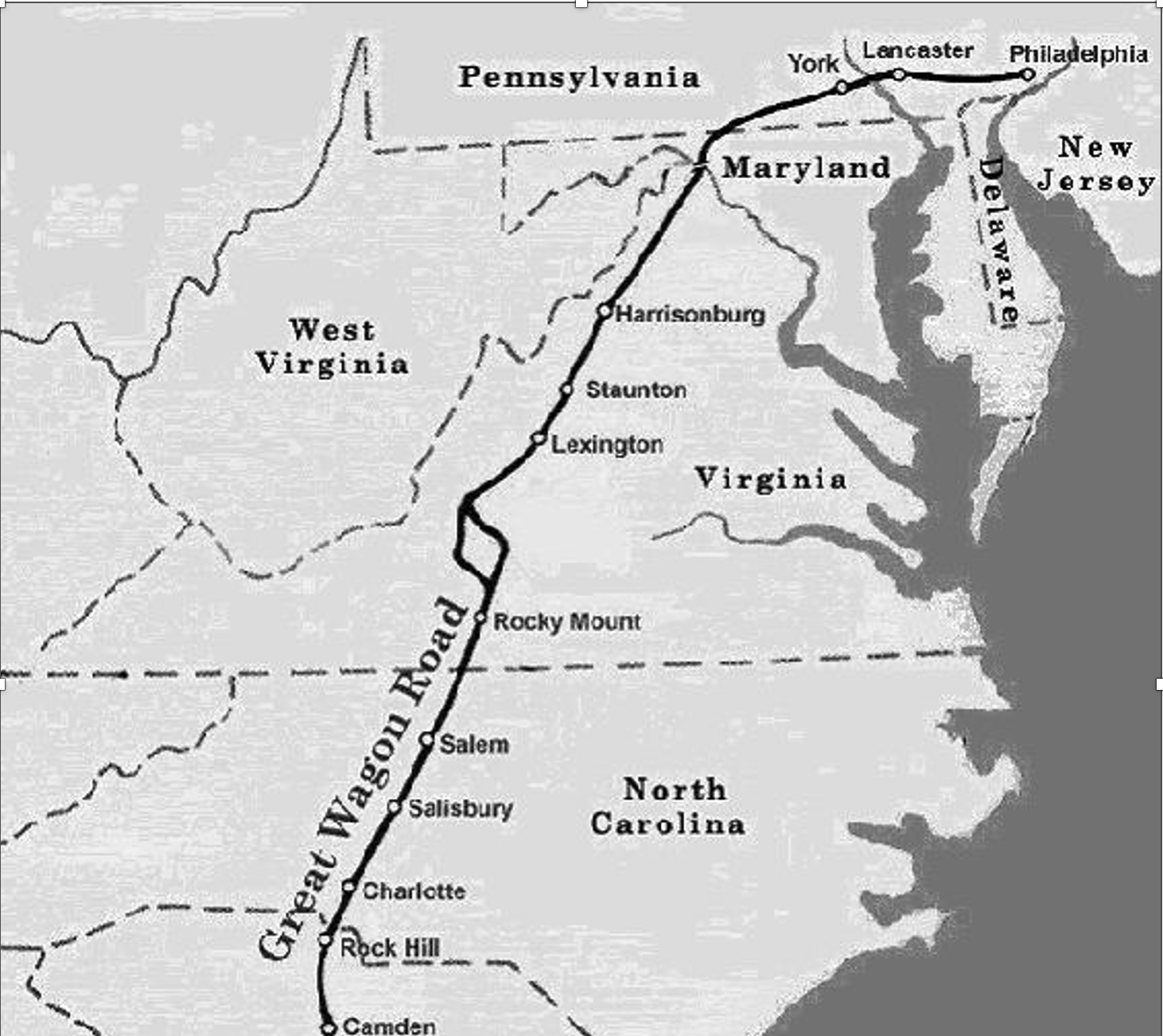

They set out on what would come to be called The Great Wagon Road that took travelers west from Philadelphia, through Lancaster to Harris Ferry (Harrisburg) to cross the Susquehanna River. (See Exhibit #1 below.) Then the road turned southwest and ran down the Shenandoah Valley until it broke east of the Blue Ridge through the Roanoke River Gap and led into the North Carolina Piedmont. At that time, however, the Great Wagon Road was still just “the wagon/Indian trail,” primitive and largely undeveloped. David Walbert describes the route:

Between Philadelphia and Salem, travelers had to cross several major rivers and steep mountain passes. Despite its name, the “Great Wagon Road” was not always easily passable by wagon! But the route from Philadelphia into the southern backcountry was not wilderness, either. There were houses, towns, and trading posts along the way where travelers could buy food for themselves and their horses.3

Long distance travel and relocating a family is an arduous endeavor in any age, but we in the modern era have little understanding or appreciation of the extreme hardships of travel in Colonial America. It was a journey of many weeks with few comforts and numerous hazards.

For people making any leg of the journey to the southern backcountry, road conditions were poor, often treacherous. Travelers experienced varying degrees of difficulty navigating roads from southern Pennsylvania through the Valley and Piedmont of Virginia into western North Carolina. Because the colonies left the maintenance of roads, even the “intercolonial” routes, to individual counties, conditions fluctuated greatly from locality to locality. Poorly marked colonial roads often caused lost migrants to lose hours and even days of valuable travel time.4

The farther south they went, the rougher the terrain and the less developed the trails. Work parties would be sent ahead to fell trees along the single-track trail to widen the path for wagons. Where flowing water had to be crossed, even known river fords sometimes had to be improved before the teams of oxen pulling the big Conestoga wagons could make it across. Work parties would attack the banks with pick and shovel…. There were tales of parties who, stymied by slopes too steep and/or slippery for the oxen, dismantled their wagon and hand-carried the wagon and its load to the summit. It was a constant process of finding a pathway, of doing whatever it took to go down it, of sniffing out a way forward.5

1 Long, p. 25.

2 Ibid. 26-27.

3 “Mapping the Great Wagon Road,” NCpedia: Colonial North Carolina (1600-1763), Settling the Piedmont. Walbert adds, “Roads are remarkably persistent. Once a road is established, towns and businesses spring up alongside it to serve travelers, and then more people travel the road to get to those new towns. Today, Interstate 81 follows the path of the wagon road from Harrisburg south through the Shenandoah Valley, and Interstate 85 follows the route of the Indian Trading Path from Petersburg, Virginia, southwest through North Carolina and into Georgia.”

4 Long, 29.

5 Michael Sheehan, “The Wagon Road, Pt. 1: Flooding the South” from the Moving North Carolina blog (MovingNorthCarolina.net).

3

Opequon Creek

The emigrants made their way finally to Orange County, Virginia. On paper it was a county. In reality it was a vast wilderness claim created as a legal entity in 1734, originally bounded by the Mississippi River to the west, the Great Lakes to the north, and the piedmont of the Appalachians in the east. The migrants settled in the vicinity of a crossing of the Opequon Creek. In 1738, more rational, surveyed boundary lines were imposed, and Frederick County was created along with several other counties as Orange County was whittled down to a more manageable size.1

The first order of business for the partnering families would be to find a parcel of land to settle, then to build a home. According to Persson, “In the early years of settlement, family-owned farmsteads formed the basis of a community, which existed in place of an organized town.”2

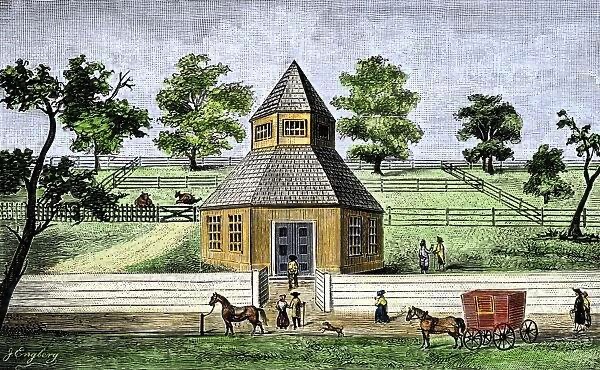

There were two distinct ethnic groups who began settling this region, Scots-Irish and German, plus the Quakers with their own religion-based culture. But interestingly, “no ethnic clusters were established… Instead, the focus was on the land and making use of natural resources. The farmsteads were situated so as to take advantage of the possibilities the new land offered, with consideration of the creek being the main factor.”3 Religion was one of the significant gathering points for the growing population of the Valley. The Scots-Irish were Presbyterian, the Germans Lutheran. The Quakers were another thing altogether and, led by Alexander Ross, this vigorous group built the Hopewell Friends Meeting House in 1734.4

There in the Opequon corner of Orange County, Virginia, the Nations and the Robinses made the acquaintance of Hezekiah Vickery (also spelled Vickory and Vickrey) who had traveled with his wife Merci and their five sons5 to seek their fortune in the untamed Valley of Virginia. It is clear that the families developed a close relationship. In particular, Hezekiah's teenaged son Marmaduke quickly took notice of John Nation's oldest daughter Elizabeth. In 1734 the 19 year-old young man took the 15 year-old girl to be his wife. If Vickery family genealogists are to be believed, their first baby, Joseph, was born the following year, followed by Christopher in 1739.

Hezekiah and his wife were not to be long-lived in their new home, however. They both took sick and died in 1736, Hezekiah at age 53, Merci at 43. John Nation was a witness to Hezekiah's last will and testament and death on October 13, 1736. It is John's first documentary mention in what was then still Orange County, Virginia.6

It was not the last. There is plenty of evidence of John Nation's active citizenship in this new home. In 1739 he signed a petition for a wagon road from “Just Hytes (Jost Hite's) Mill"7 to Asby's Bent Fork, on the Shenandoah in 1739. In 1741 he was appointed a constable.8 On 10 Sep 1749 he was appointed overseer of the road in Frederick County from the run by his house to Kerseys Ferry and charged with keeping it in good repair.9

Meanwhile, Joseph and Elizabeth Robins added another boy to their family. John Robins was born there in the Virginia frontier in 1735. They also suffered a sad loss. 22 year-old Daniel Robins died there in 1739, unmarried as far as we know.

1 Persson, 18.

2 Ibid. The homes the settlers built for themselves were log cabins, “with covers of split clapboards, and weight poles to keep them in place. They were frequently seen with earthen floors; or if wood floors were used, they were made of split puncheons, a little smoothed with the broad-axe.” Ibid., quoting Samuel Kercheval, 20. Ibid. 26-27.

3 Ibid., 19.

4 Ibid., 25.

5 Some genealogies list up to nine or ten children, but the dates and places of birth given for some make it improbable—and in at least one case impossible—for them to belong to this family.

6 Author unknown, “About John Nation,” posted on Ancestry.com.

7 “By 1738, Frederick County was established, ending the need for travel to the distant courthouse. In 1743, justices of 62 in Frederick County, Virginia, peace were established for Frederick County. Hite had served as a justice as early as 1734 for Orange County.” Persson, 18.

8 Orange County, Virginia Order book 3:7, p 152.

9 “About John Nation,” op. cit.

4

Christopher Nation Finds a Wife

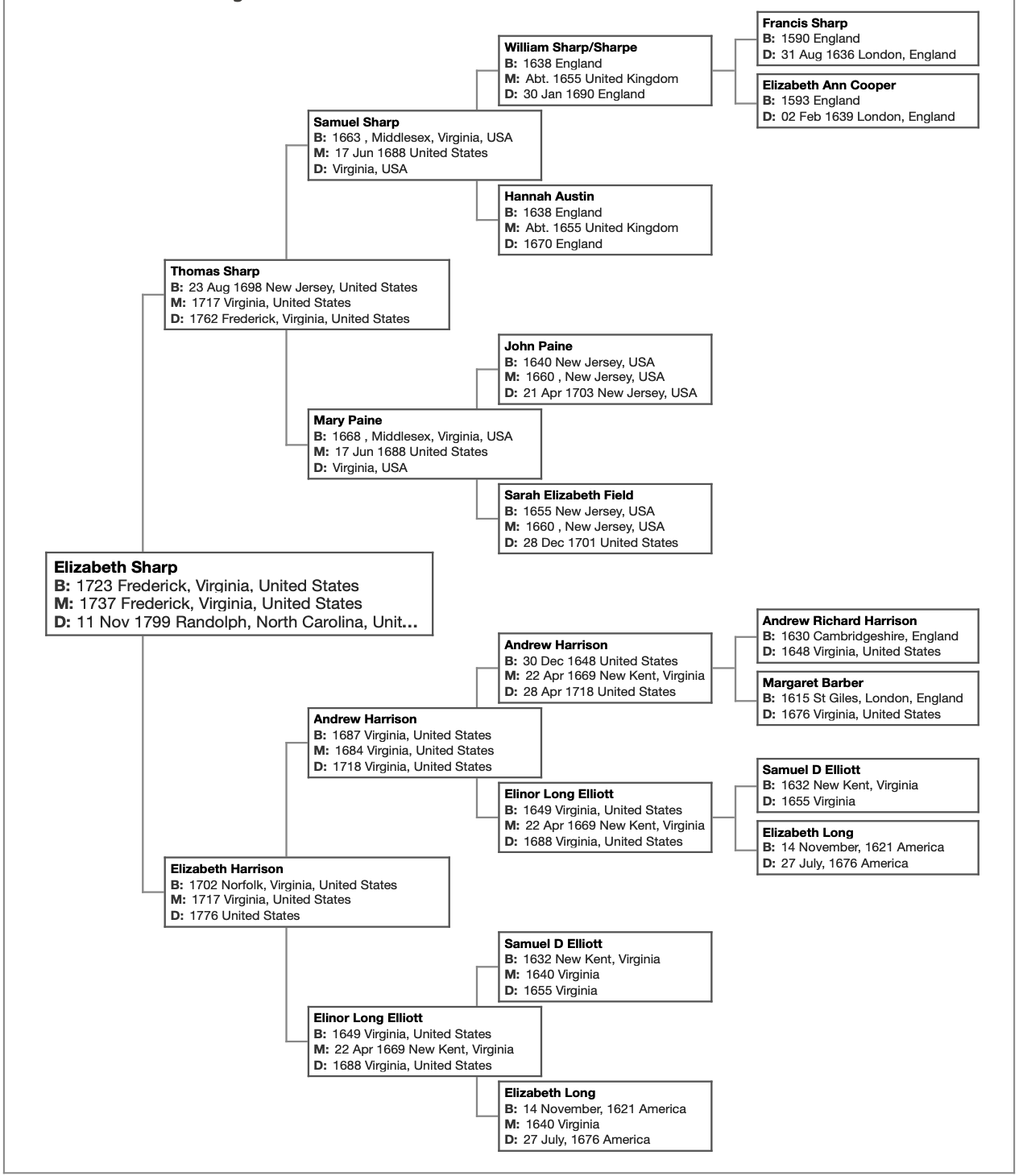

John and Bethiah's other children were also coming of age during their time in Frederick County. In 1737, 18-year old Christopher took 14-year old Elizabeth Sharp, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Sharp, to be his wife.1

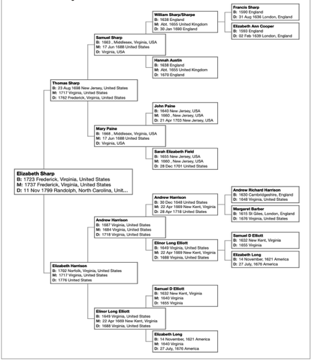

Thomas was the son of Samuel Sharp, a young Quaker who immigrated from Northampton, England to East New Jersey in 1685. There is some confusion about how many wives he had and when he married them; but he apparently married New Jersey-born Mary Paine in 1688, and Thomas was their fourth child, born in 1698. Samuel Sharp's family was apparently among the first Quakers to migrate south to Virginia. It was there that Thomas wed Virginia-born Elizabeth Harrison (some say on August 1, 1711 when he was 13 and she 11, but I think more probably in 1717 when he was 19 and she 16),2 probably around Norfolk. They were among the earliest settlers in the western Virginia wilderness, which is where their children were born—including Elizabeth in 1723.

When the Nations arrived at Opequon Creek they became near neighbors to the Sharps and developed a relationship with them as well as with the Vickerys. This closeness is documented on a lease between two men recorded in Frederick County that was witnessed by John Nation, Thomas Sharp, Jr. and Marmaduke Vickery.3 In this context, we can well understand the attraction between two young people in a small, insular society in which youthful marriage was approved, even encouraged.

Christopher Nation's young bride Elizabeth was fertile, and the newlyweds did not waste time starting their family. Their son Abraham was born the following year in 1738. That same year Elizabeth and her mother had overlapping pregnancies, so Elizabeth also gained a new baby sister.4

In 1741 their second son Christopher, Jr. arrived.5 The following year they had a daughter Nancy who, sadly, died in infancy. But in 1744 they had another son, John.6 Afterward three more children were born in Virginia: Thomas (1747) and twins Joseph and Elizabeth (1750).7

Regarding military service, in 1744 Christopher is listed in the fee book Col. James Woods of the Frederick County Militia for 55 pounds of tobacco. It probably was payment for service or a reimbursement of some sort, but it may have been an assessment.

In 1745 Christopher's 24-year-old twin sister Anna married John Buller (Bullar/Bullard), and that same year gave birth to a son, Joseph. It is somewhat uncertain who John Buller was. Some sources list his birthplace as New Jersey, others Ireland. His death date is also uncertain, except that he and Anna produced two more offspring, Moses (1750) and Isaac (1752). But unlike their older brother, those children were not born in Frederick County, Virginia. But we're getting ahead of ourselves.

Another Quaker wedding took place in the Nation family in 1745 when 20-year old John, Jr. made declarations to his 22-year old first cousin, Bethiah Robins. These young people had grown up together, but unlike their siblings were in no hurry to tie the knot as teenagers. I imagine an easy relationship of friendship and kinship between them along with a bond of fondness and affection. Soon afterward they had a son, Joseph. Sadly, Bethiah, namesake of her aunt, died in Virginia in 1750. It must have broken John's heart. He never remarried.

And yet another marriage between cousins was sealed in 1747 between John Nation, Sr.'s 20-year-old daughter Bethiah (named after her mother) and 17-year-old Joseph Robins, Jr. They had twin girls born that year, Isabel and Nancy, and two years later a son, Matthew.

In 1748, John was contacted by his brother-in-law Jacob Robins back in Monmouth, New Jersey who wanted to sell land that was still in John Nation's name. The conveyance of title was signed by Christopher representing his father with power of attorney.

1 A large number of family genealogists, perhaps even a majority (certainly those investigating the Vickery family tree), vigorously contest this fact and insist that it was Elizabeth Swaim (of a different family line, not just a variant of name) that Christopher married. Resolving this issue was one of the real hurdles that slowed the research and writing of this chapter. Nevertheless, there is definitive evidence in the will of Thomas Sharp(e), dated January 13, 1762 in Frederick County, Virginia, identifying Elizabeth Nation as one of his married daughters. Source: “Will of Thomas Sharpe 13 January 1762,” Virginia, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1652-1900. There is an Elizabeth Swaim who marries a Nation man later on, and I think that is where the confusion arrives.

2 Married Well and Often: Marriages of the Northern Neck of Virginia, 1649-1800, p. 324; Family Data Collection: Individual Records.

3 Nationstudy.com, S.V. “SHARP, Elizabeth.”

4 Viz., Jane Sharp. Then in 1740 her mother gave birth to twins William and Mary (after the late but well-remembered English monarchs); and in 1741 in another overlapping pregnancy with Elizabeth, she had Esther.

5 According to many family trees, Christopher and Elizabeth relocated to the North Carolina Piedmont, possibly along with his cousin Richard Robins, almost a decade in advance of the rest of the Nation clan. But I've found no documentary evidence of that and much circumstantial evidence that seems to make it unlikely. More in Chapter 4.

6 Many family trees list him as John Anderson Nation, with a middle name (some with the middle initial A.) that distinguishes him not only from the line of “John Nations” that extends back to the 16th century, but also from the other members of his family who did not bear a middle name—not to mention distinguishing him from the naming conventions of that era. I have found no record or story about it, and no notice of someone named Anderson after whom he might have been named—or even how the memory of that name has been preserved. I am dubious. In this account he will simply be called John. However, Christopher did have a grandson named John Anderson Nation—the child of his next-to-youngest son, William.

7 There is an anomaly in the family records; many of the Nation genealogies record the birthplaces of Joseph and Elizabeth in two different places a hundred miles apart (Franklin and Augusta) despite being twins! I have chosen to regard the Franklin birthplace as authentic since there is no other evidence that Christopher and Bethiah ever dwelt in Augusta, but Bethiah may have given birth to the twins there en route to North Carolina. NationStudy.com, shows Elizabeth to be born later, in 1757 in North Carolina, and that is possible, but I think the earlier birthdate has more evidence.

7 “By 1738, Frederick County was established, ending the need for travel to the distant courthouse. In 1743, justices of 62 in Frederick County, Virginia, peace were established for Frederick County. Hite had served as a justice as early as 1734 for Orange County.” Persson, 18.

8 Orange County, Virginia Order book 3:7, p 152.

9 “About John Nation,” op. cit.

5

A New Deal

John Nation had cleared a spot and farmed it for more than fifteen years without a formal deed. In October 1748, Thomas Lord Fairfax agreed to honor all previous land grants made by the "Colony of Virginia" that were within his Proprietary. It was not an act of grace, but a way to develop his lands and collect ground rents.

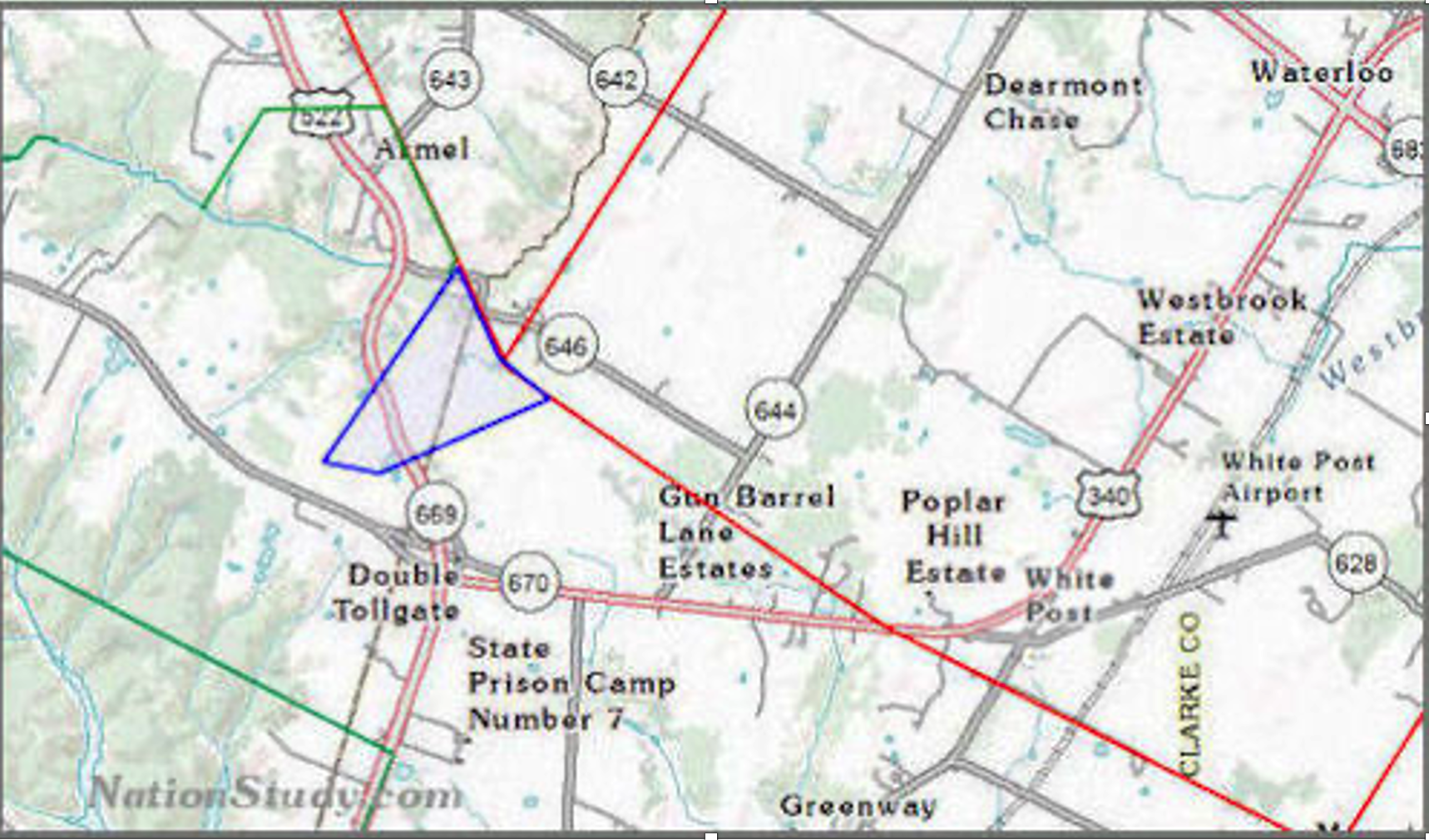

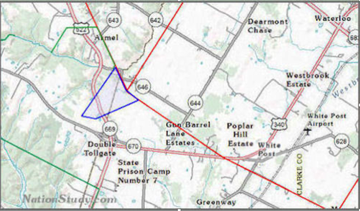

On October 1, 1749 Fairfax issued John Nation a 188-acre land grant on Opekon Run (Creek) in Frederick County in the northern neck of Virginia.1 His land contained "John Nation's Spring," a resting place for travelers. This spring appeared on the first survey of the area, which means that John probably met young George Washington who surveyed the area for Lord Fairfax. Using the deeds of John Nation and Lord Fairfax's nephew, the author of the online Nation Study has plotted John's grant about 10 miles south of Winchester, Virginia at the end of State Rte. 646—which still bears the name Nations Spring Road. “Nation's Spring is mentioned in both Deeds. In fact, John's land was known as Nations Plantation for over 20 years after he left for North Carolina….”2

It was the first land John owned for which we have a record. It would seem that he had finally found his permanent home. But on December 5, 1750 he sold the land back to Lord Fairfax for £85 Virginia money.3

We can only wonder if John Nation planned that turnaround ahead of time or if his attention was drawn elsewhere after he had received the grant. We might also wonder whether there might have been some influence of the growing unrest with the French encroaching on territory claimed by Virginia and the British Crown in the Ohio Valley. That was also accompanied by an increase in hostile activity against white settlers by the Shawnee. Putting some distance between those tensions and themselves may have been as much a motive as the quest for prosperity.

What we know is that in 1751 John Nation took his family from Frederick County, Virginia to what would soon become Rowan County, North Carolina. Once again, the Nations were joined by the Joseph Robins family but possibly not yet by their son-in-law Marmaduke and daughter Elizabeth. There are conflicting stories, some which have the young Vickery family together with the Nations in North Carolina, and others that assign the birth of at least three, perhaps four more children to Virginia through 1752. I am inclined to believe that they all came down together and that the supposed Virginia births are mistakes. We can confirm, however, that they were all together in North Carolina by 1758.4

1 John Nation's Deed, Nation Study (nationstudy.com):

Virginia Northern Neck Land Grant - Frederick Co.

Acquired 188A 1 Oct 1749 (known as Wright's Run then Nation's Run)

Yearly rent of £0.03s.09d

Nation's farm was located near Double Tollgate, Clarke Co., Virginia, USA See Exhibits #4 below.

2 “Stepping Forward, op. cit.

3 British currency was strictly limited by the Crown and scarce in the colonies, so each colonial government set exchange rates for legal tender, called “proclamation money.” Virginia pounds were generally valued about 75% of sterling.

4 North Carolina, U.S., Compiled Census and Census Substitutes Index, 1790-1890.

6

Better Prospects in North Carolina

European settlers in North Carolina kept to the coastal plain for the first 130 years of the colony's existence. There were few byways into the back country and the rivers were not conducive to trade and travel. The impetus for expansion into the Piedmont came not from the English along the coast, but from the Scots-Irish and Germans coming from the north down the Great Wagon Road. That's a movement that began in the 1730s. By 1750 there were new areas ready to be opened and opportunity-seeking settlers ready to move into them.

Amid the large numbers of Scots-Irish and German immigrants who were flowing into the area at this time, there were also notable movements of Quakers. Here, as opposed to Frederick, Virginia, the groups settled more protectively in ethnic and cultural enclaves. In 1751 the Quakers established the Cane Creek Monthly Meeting in the Cane Creek Valley and in 1754 the New Garden Meeting near present day Greensboro. But it should be noted that two other religiously oriented groups also migrated to that same area: the Moravians in 1753 who founded Bethabara and later Salem; and some families of Baptists from New England in 1755 who settled near Sandy Creek where they established what became the mother church of the Separate Baptist Movement that exploded throughout the South. All of these special expressions of the Christian faith reveal how the whole neighborhood was characterized by spiritual awakening and fervor that was bound to have influenced the Nation-Robins clan.

John Nation was 54 when he and his brother-in-law Joseph Robins led their families to a new home and new prospects in North Carolina. His wife Bethiah was 49. With them were unmarried Eleanor (34); Christopher (30) and his wife and six children, including the recently born twins, Joseph and Elizabeth (b. 1750); Anna (30) and her husband John Buller with their child Joseph; Joseph Nation (26), also unmarried; John, Jr. (25), now a grieving widower with a son; daughter Bethiah and son-in-law Joseph Robins with their youngster; and Frances (22 or 23), also yet unmarried. Joseph's sons, 30 year-old William and 26 year-old John (marital status unknown), also apparently made the journey. Several members of the Vickery family also apparently made the migration further south around this time.

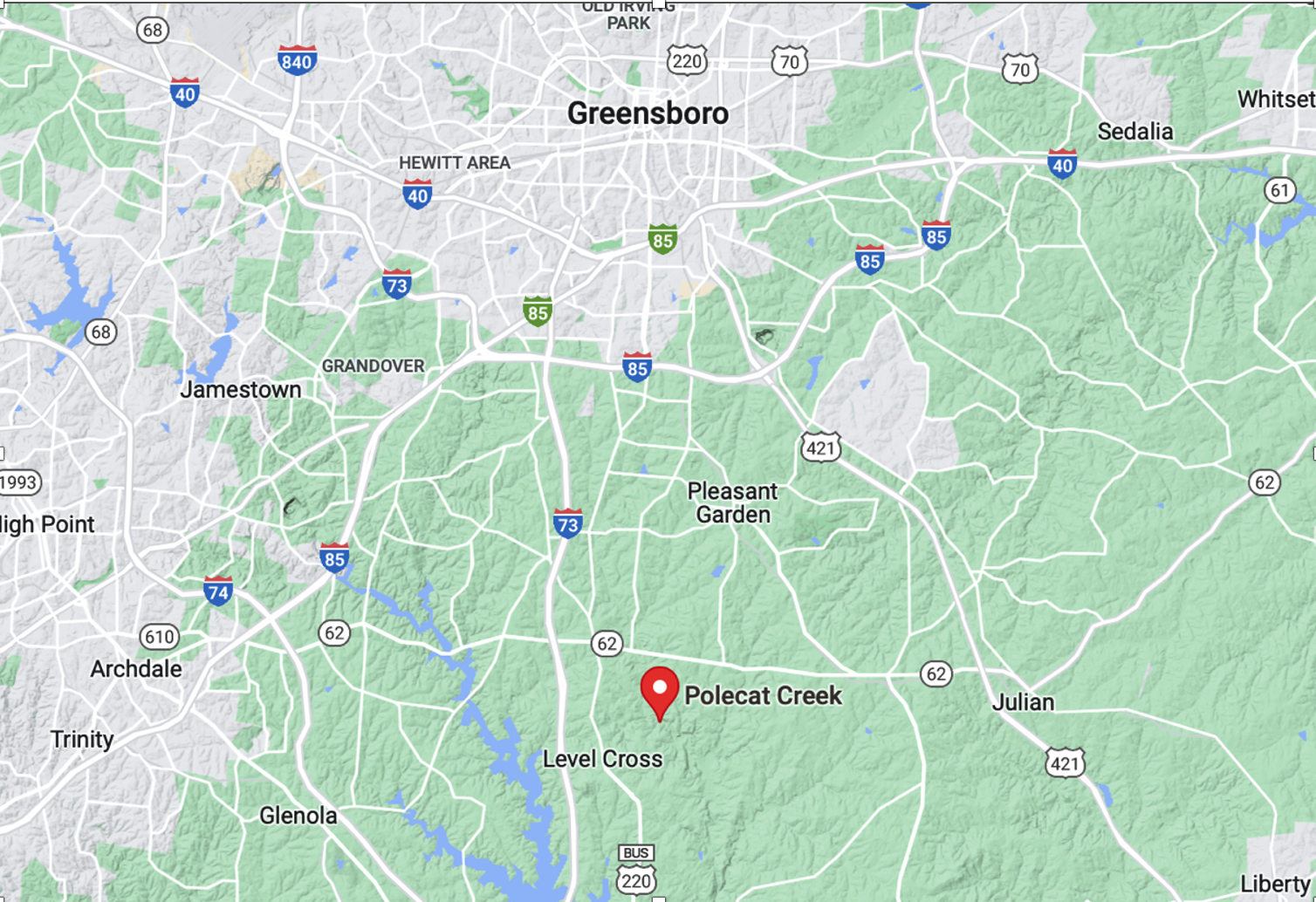

Once again demonstrating their affiliation with the Quakers, the Nation and Robins families settled in the area favored by that sect.1 John picked an area between Polecat Creek and Deep River on a headright grant from Lord Granville near the settlement called Capefair. Indigenous tribes had occupied the area for centuries, and Quaker settlers had been arriving since 1750. More than 50 years later it would be constituted a town and renamed Greensboro. It took some time, and deeds and title would follow later, but the Nation-Robins clan secured substantial acreage of fertile farmland. When Rowan County was created as a legal entity in 1753, John Nation was already there as one of its charter citizens.

1 Sheehan, “The Great Wagon Road, Pt. 2: Shaping North Carolina,” op. cit.

7

Captain John Nation

When the French and Indian War broke out in April 1754 the governors of the British-ruled colonies called for the formation and mobilization of militias. Now, the reader will note that I have never identified John Nation as a Quaker, but only pointed out that his movements and associations indicate strong ties with the Quakers. Whatever his personal commitments to the movement may have been, his affiliation with them was about to be broken, for John Nation accepted the governor's appointment as a Captain of Militia under Colonel Francis Corbin—as did also his brother-in-law Joseph Robins. His son Christopher was made a lieutenant and his son John, Jr. an Ensign.1

We have no way of knowing how many relationships were broken by this act, but we can imagine the tensions that were raised. For example, in 1756 the North Carolina Assembly passed a draft act “requiring every twentieth man in each county to be drafted and sent to the frontier to fight in the French and Indian War. Those who refused were to be court martialed” –and they declined to exempt Quakers. Those who held to their convictions paid a price for it.2 At best there must have been a severe cooling of relationships between the Nations and their Quaker friends. If the Nations and Robinses actually had been practicing members of the Society of Friends, their military commitment would be regarded as a defection and betrayal.

We do not have a specific military record for Captain John Nation and the rest of his family. We do know that while North Carolina did send some men north to fight under British command, this colony's greater concern was infiltration and attack by Shawnee war parties. For this threat the Cherokee were an effective buffer. But after Cherokee warriors were badly used in northern campaigns while treaty promises went unfulfilled, relations with that tribe began to turn sour. In the later days of the war the Cherokee were a greater threat than the Shawnee.

Meanwhile, “between 1755 and 1757 North Carolina concentrated on shoring up its frontier defenses…. In 1758 refugees from the western frontier and the north streamed into North Carolina to escape the war,” and “in 1759 a significant number of Cherokees turned against the English.”3 It seems most likely that our ancestors had skirmishes with Native American foes, defending their own homes as opposed to serving imperial aims against the French.

Death of Joseph Robins

Captain Joseph Robins, 58, would see little of the conflict. No bullet, tomahawk, or arrow took him down.

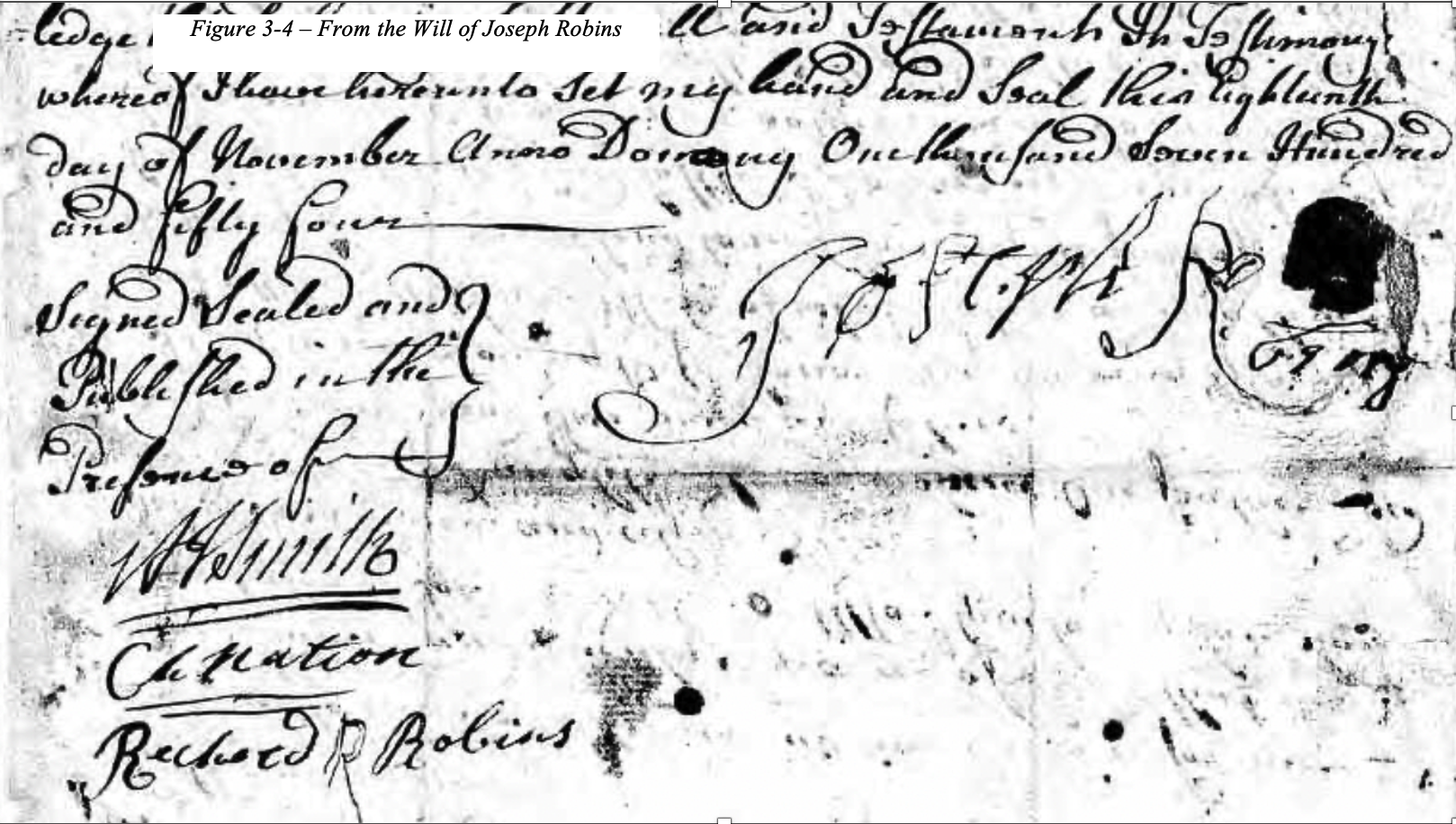

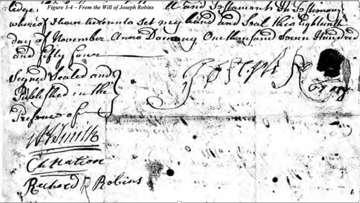

In the name of God Amen, I Joseph Robins of Rowan County in the Province of North Carolina being at this time very sick and weak in body but thanks be to Almighty God of Sound Sence and Memory and knowing it is ordained for all men to Die, I have thought fit to make my last Will and Testament…. First and Principally I commend my Soul into the hands of Almighty God who gaveth me hope seeing that through the Meritorious Death and Passion of my Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ I shall receive the Glorious Resurrection. And as to my worldly Estate that it hath pleased God to Indow me with I give and bequeath in Measure and Form following….4

The will, signed and witnessed on November 18, 1754, gives us a glimpse of a man who is comforted in his final hours by a vital faith in the Savior and the ardent love of his family—and especially his beloved Eleanor, whose every mention in the will is with the epithet “my loving wife.” The worldly goods that he dispenses to his heirs indicate how much he had prospered, including a 400 acre plantation “called the old place” and another 266 acre plantation “where I now live,” along with several head of livestock and sundry pieces of furniture.

As executors Joseph appointed his “loving wife Elenor and my brother in Law John Nation.” Witnesses to the will included Christopher Nation and Joseph and Bethiah's younger brother Richard, who had settled in North Carolina by 1735 when his fourth son Richard (Jr.) was born. The signatures on the will are revealing. (See exhibit in Gallery below.) Joseph's signature is shaky but legible and lucid, indicating a literate man of failing strength. Christopher Nation's clear, strong hand tells us that, though his father was not literate (he signed documents with a mark) he made sure at least one of his children got the advantage of good Quaker schooling. (Note also that Christopher signs his name as Nation, not as “Nations.”)

Joseph's “loving wife Elenor” did not survive him long enough to execute the will; the 52 year-old wife and mother died shortly thereafter, likely of the same fever that claimed her husband. Late November 1754 was a season of mourning for John Nation. Within a short spread of time, he lost his best friend and that friend's well-loved wife to one of those deadly infections that arrived with the cold weather. That same month—likely the same week—it also claimed John and Bethiah's own Eleanor, their unmarried, 34 year-old daughter.

Yet, neither a season of bitter grief, nor the concerns of war, nor the loss of communion with the Society of Friends deterred John Nation from expanding and developing his holdings in the North Carolina Piedmont. Indeed, it all seemed to quicken him, even to give him a sense of urgency.

1 Murtie June Clark, Colonial Soldiers of the South 1732-1744 (U of Michigan: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1983), 635.

2 Steven Jay White, “North Carolina Quakers in the Era of the American Revolution” (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, Master of Arts Thesis, 1981), 36.

3 R. Jackson Marshall III, “French and Indian War,” NCPedia.org, 2006.

4 "The Will of Joseph Robins," North Carolina, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998, images 186-188.

8

Captain John Nation, Gentleman

John added to his holdings with two deeds by Lord Granville, one for 401 acres on Polecat Creek, the other for 403 acres on Quaker Creek on both sides of the Orange and Rowan County line, each for 10 shillings sterling. Both were proved in court on May 11, 1757 in Rowan County. In 1758 he was on the Rowan County tax rolls for 9 polls, i.e., persons (heads) in his household. On February 22, 1759, “Capt. John Nation (militia), gentleman," was granted "260 acres between Pole Cat Creek and Deep River on branches of both." Later that spring he and his wife Bethiah sold the Quaker Creek property to one Robert Fields for "20 pounds Virginia money” in a transaction that was witnessed by Christopher and John Nation. The deed was proved in court on March 16, 1759.1

In 1760 he is recognized in Rowan County, North Carolina as the administrator of Joseph Robins's estate. And in the tax enumeration of 1761 he is listed as a magistrate.

See how far the poor, orphaned servant boy has come. In childhood he had traveled the ocean. As a young family man, he led his family through hardship and peril to establish a new home in a wilderness, only to pick up and do it again two decades later. Now in his sunset years he is reaping the fruits of his faith that better days lay ahead if he took the risks. Following the example set for him by his wife's Scottish grandfather, he did not let his early bondage define him but rather used it as a springboard for his ambitions. He now has a measure of wealth and the esteem of his community. From servant boy, to pioneer, to yeoman, to captain. Now, in a registered document, he is a gentleman. In the English colonies, terms like that were meaningful, reserved, and not thrown about cheaply. It indicated the attainment of a higher status, a higher social class. From servant boy to gentleman--stories like his are the genesis of something that would later be called the American Dream.

In 1760, John and Bethiah experienced another grief, the loss of their daughter Bethiah. The 33 year-old mother left behind her husband Joseph Robins, Jr. and three children in their early teens. However, their daughter Anna and her husband John Bullar had given them three grandsons. Their son Joseph and his wife Eleanor (Robins) appear to have lost three girls in childbirth or infancy but had five strapping boys who survived and would grow to adulthood. John, Jr., as we have mentioned, remained unmarried and childless. But young Rachel, around 1754 at age 25, married 22 year-old William Robins—a New Jersey-born cousin, oldest son of Joseph's younger brother Richard Robins and his wife Anna Race Robins. From 1754-1770 William and Rachel produced eleven children, eight of which lived to adulthood.

Surrounded by his surviving children and a goodly and still growing number of grandchildren, at age 64 John Nation was probably feeling his age and the hardships of the years. It seemed good to him to assign his oldest son and heir his portion of the inheritance.

John Nation for and in consideration of the natural love and affection which he hath and beareth unto the said Christopher Nation . . . grants 174 acres by indenture, 28 May 1753 by Earl Granville and registered in Rowan Co. NC Book IV, p. 38:

Sign: John Nation [mark], Witnesses: Thomas Lamb, Jeremiah Reynolds. Recorded Apr 1761 on 18 Apr 1761 at Rowan Co., NC. 2

It was time now for Christopher to begin to take his place as the leader of the Nation family.

1 Documents quoted in “John Nation,” author unknown.

2 “Captain John Nation,” Author unknown.