Nation's Notebook

NATION FAMILY CHRONICLES

Book I - THE NATIONS

Chapter 4

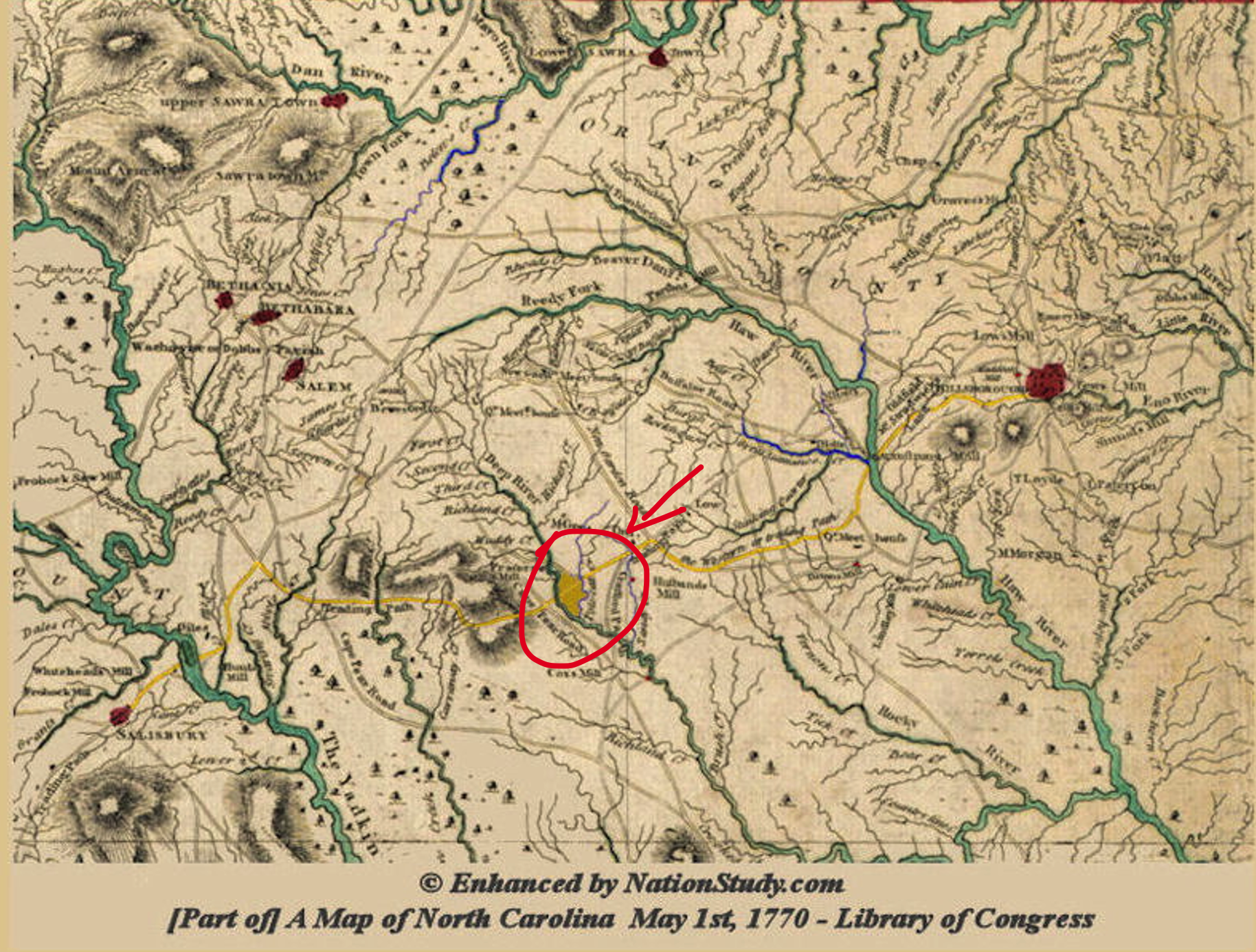

Regulators and Revolution

The Nations in the Revolutionary Era

Enter Text

Coming Soon

Chapter 5

The Settlers

1

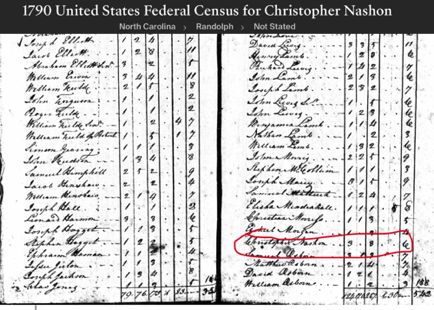

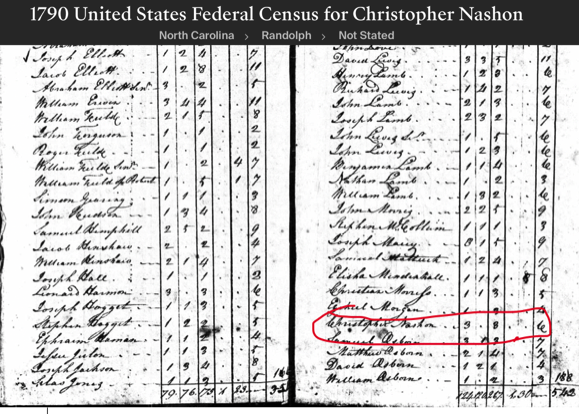

Christopher Nation in North Carolina

When John Nation led his family from their home in Monmouth County, New Jersey to the Virginia wilderness, his oldest son Christopher was twelve years old. No doubt the boy did a lot of growing up on the weeks-long, perhaps months-long trek down the rough trail that would become the Great Wagon Road. That was followed by many months of toil, assisting his father and uncle to build houses and turn raw land into a productive plantation along Opequon Creek in Frederick County, Virginia.1

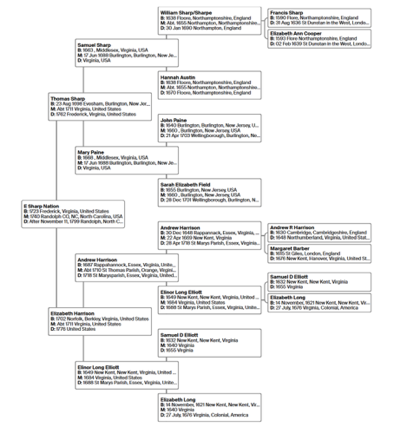

Here in 1737, 18-year-old Christopher took Elizabeth Sharp, the 14-year-old daughter of a notable member of the Quaker community, to be his lawful wife. There they had their first child, Abraham in 1738. Their second child Christopher, Jr. arrived in 1741. According to some accounts, they already been making a home in the North Carolina Piedmont, the vanguard of the migration of the Nation/Robins/Vickery clan that would transpire almost a decade later, but a fuller consideration of evidence makes that unlikely.2 For example, in 1748, Christopher represented his father with power of attorney to sign over to his uncle Jacob Robins a parcel of land in New Jersey that was still owned by John Nation—and most likely had to journey back to the old home place to do it.3 Another piece of evidence is Christopher's 1750 sale of land in Frederick County to his neighbor William Roberts. See . The boundary stone marking the property line was found with the name John Nations carved on it, per Lillian Honditch, Nov 2006. This was undoubtedly preparatory to the family's departure for North Carolina.

It is most likely that Christopher's family settled with his brothers on his father's plot of land in the Quaker neighborhood along Polecat Creek, a Deep River tributary. In 1751, he and his younger brother John were witnesses to a Quaker Wedding, the Lamb-Beeson wedding, in Guilford (soon to be Rowan, finally to be Randolph) County at New Garden.5 It is the first documented mention I have found of Christopher in North Carolina. At some point he apparently acquired land independently of his father because he and his wife Elizabeth sold 216 acres to one Benjamin Cox for 23 pounds, May 11, 1757. Ibid. Here also Christopher and Elizabeth added three more members to their family: William (1752), Bethiah (1754), and Amos (1756). According to NationStudy.com Elizabeth was not Joseph's twin but was born in Rowan, NC in 1757, Amos in 1758, and Bethiah in 1760.

In 1755 he was a Justice of the Peace for his district, newly created in1753 and named Rowan County. He is named in a list of J.P.'s that included Squire Boone (father of Daniel Boone) for the building of a new jail (“prison”) in the county seat of Salisbury. He is also listed on the tax rolls of Rowan County in 1759.

As noted in the previous chapter, he served with his father as a lieutenant of militia during the French and Indian War. We have no record of their specific service or its duration, but likely it covered at least 1755-1760 and included one or more stints manning the garrison at Ft. Dobbs near present-day Statesville, and they probably also were involved in skirmishes against the Cherokee. Indian raids had led many backcountry settlers to seek refuge at Ft. Dobbs, and in February 1760 a large war party of Cherokee attacked the fort itself and were repulsed. The governor brought in reinforcements for his provincial regulars from Virginia, but before they could mount a campaign the tribe sued for peace, ending the hostilities and, for all purposes, the war itself as far as the westerners in the colony were concerned.

1 Near present-day Winchester.

2 See the discussion in Chapter 3. According to NationStudy.com, most of the children of Christopher and Elizabeth Nation were born in Frederick County, Virginia, and other documentary evidence seems to support that fact.

3 Nation Study: Stepping Forward to 1840 in America, https://nationstudy.com/histories/step.php cites documentation that:

On 12 Dec 1748 Jacob Robins quit claims to Henry Chamberlin for a … meadow which was conveyed to him by Christopher Nation by a conveyance, dated 10 Dec 1748, "from which sd. Nation had Right to the land from his father, John Nation, by a Power of Attorney."

4 See . The boundary stone marking the property line was found with the name John Nations carved on it, per Lillian Honditch, Nov

5 “Christopher Nation,” www.ancestry.com, Christopher Nation. About 10 years later, on June 7, 1761, he witnessed also the Beeson-Lamb wedding; and he is on record of having done business with members of the Beeson family..

2

The Stressful Sixties

Finally past the worries of war and the threat of Indian attacks, the upland settlers were hoping for more prosperous times. Those hopes were challenged by a series of droughts that hurt crop production and drove many poor farmers into debt. The economic troubles set up a decade of discontent that aggravated social inequities that moved into politics and beyond. The 1760s were a stressful and turbulent decade for the farmers and planters of the Piedmont as a whole, and the Nation family felt many of those stresses.

John Nation, Sr. decided in April 1761 that it was a good idea to transfer some of his property on Polecat Creek to his oldest son, including a 174-acre plot of land “adjoining Widow Lamb” that Christopher sold at some point later. The fatherly intention for the bequest is clear: “…for and in consideration of the natural love and affection which he hath and beareth unto the said Christopher Nation….” It was an early distribution of his inheritance. One of the witnesses was neighbor Thomas Lamb.1

Grief was a part of Christopher's family life in these early years of the decade. His 33-year-old sister, a mother of three, died in 1760. His wife Elizabeth lost her father Thomas Sharp, still back in Frederick County, Virginia, in January 1762.

Thomas Sharp left a will dated 13 Jan 1762 and proved 6 Apr 1762 in Frederick County, Virginia, reading in part:

"I give and bequeath to my daughters Rebecca Churchman, Elizabeth Nation, Sarah Love, Ann Haines, Jane Hankins, Mary Ramey and Mary Frazier one shilling Sterling Each of them to be paid in six months after my Decease and that they have no other part of my Estate. I give and Bequeath unto my Daughter Easter Sharp the sum of twenty Shillings current money to be paid in six months after my decease and to have no other part of my Estate." [sic]2

However, with three sons entering their twenties and one in his teens, Christopher apparently was able to let go of many of the day-to-day concerns of farming and turn his attention more to community affairs. As a justice of the peace and an officer in the militia—now a Captain3—he had a clearer view than most of the growing corruption of the government and the simmering grievances of the populace.

In truth, there were two colonies in North Carolina now: the well-established, urbanized, more densely populated, and very English coastal colony; and the upstart, fast-growing but still sparsely populated, rural, Scots-Irish western colony of the Piedmont. Their interests and culture were widely divergent, but they were under the same government dominated by the coastal aristocrats. There were no elections; all government officials were chosen by the Royal Governor from his capital in New Bern.

The westerners complained of unfair and arbitrary taxation, illegal fees, and corrupt officials. A particular grievance was the notorious “courthouse ring,” a wealthy clique that dominated the political and legal affairs of the region. The ringleader was Edmund Fanning, the Crown Attorney and land speculator who orchestrated abuses of power with impunity by area sheriffs and magistrates. These included charging colonists with high fees and fines, often invented to enrich the officers and the governor.4 As rising protests of individual citizens fell on deaf ears, tensions rose to the breaking point.

1 “Christopher Nation,” www.ancestry.com, Christopher Nation.

2 This is more documentary evidence that it was Elizabeth Sharp (not Swaim) that Christopher married.

3 Presumably for the Polecat District. in Col. Alexander Osborn's 4th Regiment of Foot, Rowan County, North Carolina provincial militia Muster Roll of 21st Nov 1766.

4 “Primary Source: The Regulators Organize,” NCPedia.org.

3

The Regulators vs. Gov. Tryon

In 1766 the colonial legislature gave the new governor, William Tryon, permission build a new “Government House” and a first allotment of 5,000 pounds to be paid for by raising the poll (or head) tax. To the Piedmont farmers, the governor was building a “palace” on their poor backs. Adding to the injury, in 1768, the legislature boosted the sum to 15,000 pounds. Comparable to about $3.5 million.2

Individual appeals had gotten them nowhere. The Stamp Act protests of 1765 throughout the colonies showed the power of organized action. So inspired, “Piedmont farmers first organized in Orange County in 1766, coalescing around the principles preached by a Quaker named Herman (or Harmon) Husband.” Husband, an able grassroots communicator who ardently followed Benjamin Franklin, actually did not consider himself a leader but rather a facilitator and mediator. But “Husband's powerful ideas about social justice combined religious radicalism with the country or real Whig political philosophy increasingly adopted by the Patriot movement.”2

By 1768 they were actively recruiting members to regulate and reform government abuse, and calling themselves “Regulators,” a term coined in England a hundred years before.

We the under written subscribers do voluntarily agree to form ourselves into an Association to assemble ourselves for conferences for regulating publick Grievances & abuses of Power in the following particulars with others of like nature that may occur…. “3

At first following Husband's ideals of peaceful protest, the Regulators began by presenting appeals to local officials, the governor, and the colonial assembly to no avail. They brought lawsuits against corrupt officials, but the courts were rigged and their cases all failed. They tried passive resistance, refusing to pay the taxes only to have their property seized for public sale. They responded by forcibly repossessing their property, disrupting court proceedings, and putting officials on trial in people's courts. When a group of Regulators rowdily disrupted the proceedings of the colonial court at Hillsborough in September 1768, Gov. Tryon confronted them with a company of militia and dispersed it without further show of violence. After this episode, a group of twenty-one Regulators, Christopher Nation among them, presented a signed petition to the governor:

"Whereas through the exactions and extortions of several officers of Orange, we have involved ourselves in many difficulties and by means of reports, false spread, the condition has arose to a great extremity and being desirous to submit ourselves to the clemency of your excellence, and to lay aside all method of redress of our grievances, but by a due course of law, and beg that your excellence will forgive all our past offenses by your gracious proclamation, that peace and tranquility may be restored again, to all the inhabitants of this province, and confiding in your assistance and favor to execute the laws against said exactions and extortions and conclude."4

On October 3, Tryon responded with a show of magnanimity:

I do, therefore, out of a compassion for the misguided multitude, being much more inclined to prevent than punish crimes of so high a nature by and with the unanimous advice and consent of his Majesty's Council issue this proclamation granting unto them His Majesty's most gracious pardon for the several outrageous acts by them committed at any time before the day of the date hereof, except James Hunter, Ninion Hamilton, Peter Craven, Isaac Jackson, Harmon Husband, Matthew Moffit, Christopher Nation, Solomon Cross and John Oneal, of which all officers of Justice and others concerned therein are to take notice. 5

Christopher and the others did eventually get their pardon on September 9.

The Regulators—at least a faction of them—tried again to follow the legal route. On May 6, 1769 Governor Tryon ordered the Assembly dissolved and elections took place on 18 July 1769. A few of them, along with Husband, got elected to the House of Burgesses. JP Christopher Nation was one of the men elected to represent Rowan County. (It was during this session that Guilford County was formed from parts of Rowan and Orange Counties.) Arriving to the session in December, Christopher was paid a total of £12.18.6 for eighteen days of attendance and sixteen days of travel. He also got mentioned—disparagingly—in correspondence to and from England between Col. John Harvey in North Carolina and Henry Eustace McCulloh in London. The latter wrote back to Col. Harvey, "I thank you for the journal of your political proceedings… The madness of the people must be great indeed, to trust such wretches as Harmon Husbands and Christopher Nation, as their representatives—but it is a comfort, that violent mad fits seldom last long."

The presence of Regulators (or persons representing them—Husband denied being a Regulator) in the legislature was as ill-received as the attempt to take over the court in Hillsboro. For all his efforts to be winsome, Husband was accused of libel, expelled from the assembly, and jailed. Soon afterward the assembly passed a Riot Act authorizing the governor to use military force against “rebellion” along with other measures directed toward the Regulator movement.6

Considering the experiment to bring changes by the law to have failed, the Regulators once again turned to aggressive actions.

1 “The Regulator Movement,” NCPedia.org.

2 Encyclopedia.com, S.v. “Regulators."

3 Primary Source: The Regulators Organize,” op. cit.

4 “Petitions to Lord Tryon.” https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/27990708/person/5110523799/media/61be6103-349e-45a6-8bc4-20402d6923c6

5 Ibid. But the author of NationStudy.com (“The Regulators of Colonial North Carolina: The Case for Christopher NATION Jr.” NationStudy.org. ) believes the Christopher Nation mentioned here must be Christopher, Jr.; that it is unlikely that a man so tarnished by recent rowdiness would continue to be approved to be a Justice of the Peace. And Junior, around age 29/30 would have been a better candidate for such aggressive activism. However, Harmon Husband, though under the same early ban, had no problems being elected to the House of Burgesses. I would say at this point that The NationStudy proposal is interesting and plausible and reasonable, but not yet persuasive. I do believe there is some likelihood that Christopher, Jr. took an active role in the Regulator Movement and Rebellion. But I am not ready to agree that Jr. has been mistaken for Sr. here.

6 “Primary Source: An Act for Preventing Tumultuous and Riotous Assemblies,” NCPedia.org.

4

The Resistance Turns Violent

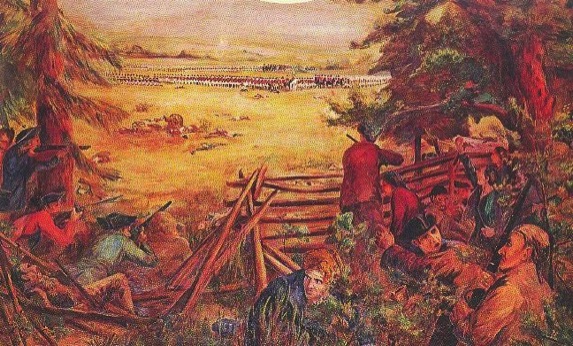

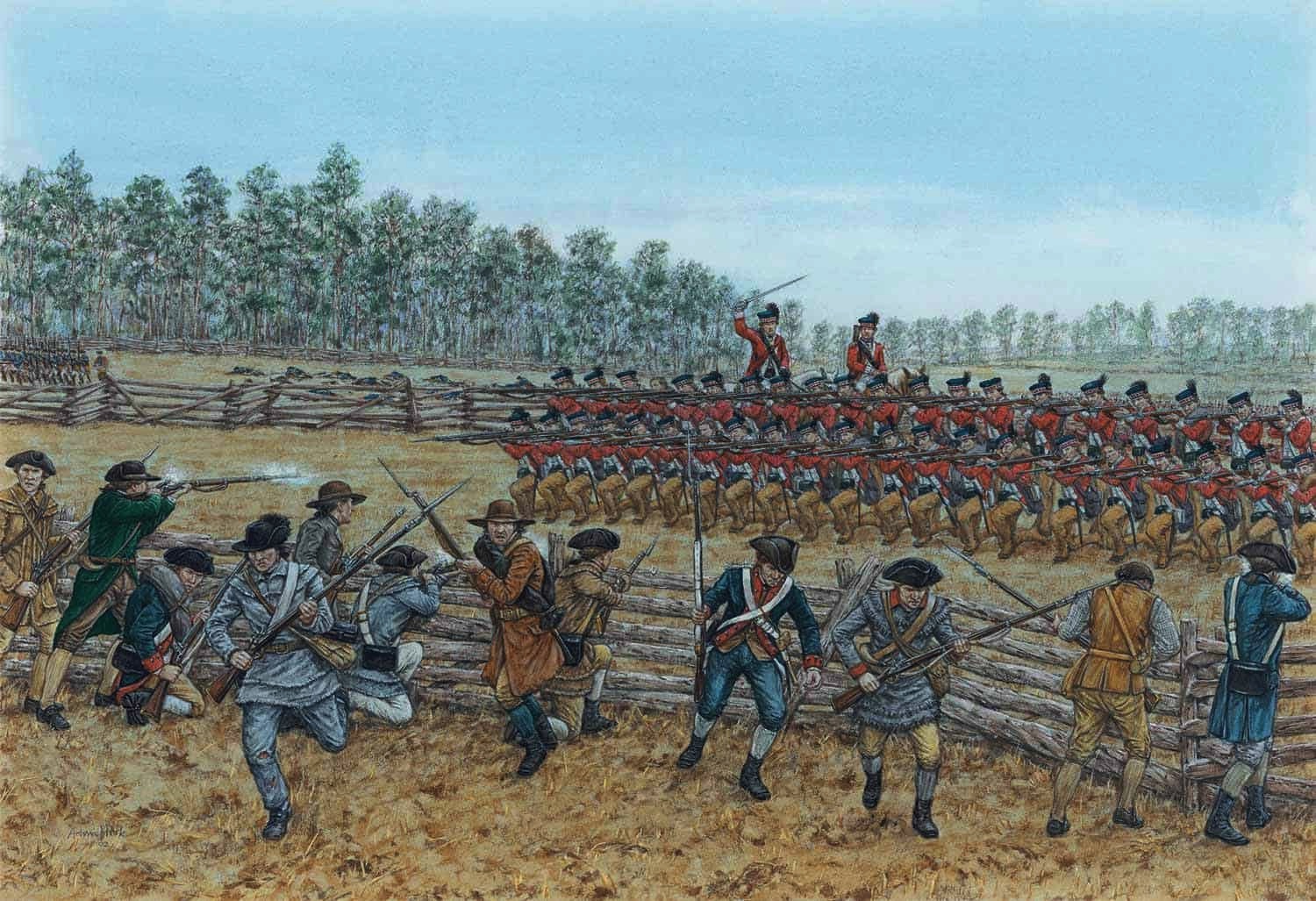

In September 1770, with many Regulator cases on the court docket, about 150 Regulators showed up in Hillsborough, many of them “conspicuously armed.”

Tensions boiled over and turned into a riot, with the Regulators beating up “a number of lawyers, merchants, and officials,” severely beating the much-despised Edmund Fanning, and destroying his home. It was a provocation Gov. Tryon could not ignore. Relying on powers given him by the Riot Act he raised a militia, then made his move. The Regulators at this point were a host of farmers with impressive numbers but no one in command.

From Encyclopedia.com:

On 16 May 1771, about eleven hundred militiamen, commanded by many of North Carolina's prominent Patriots—men who would soon lead North Carolina into independence—confronted upward of two thousand farmers on a field near Alamance Creek, about twenty miles from Hillsborough. In a battle that lasted less than two hours, from 17 to 20 farmers were killed along with 9 militiamen; more than 150 men on both sides were wounded. One Regulator was hanged on the spot without benefit of trial. Six more were executed on 19 June in Hillsborough after a hasty trial. After the battle, the governor and his troops undertook a punitive march through the Piedmont, forcing some six thousand men, the great majority of adult males in the area, to take the oath of allegiance to the crown. Some of the best-known Regulators fled the province, and by summer the Regulation had been suppressed.1

Was Christopher Nation—or Christopher, Jr., or any of the Nations—involved in this battle? That is not known. The battle took place only about 20 miles east of the Nation family farms. However, the Nation name does not appear in any other record having to do with the Regulator “rebellion.” Tryon's men destroyed properties of those considered the ringleaders, but if the Nation land was touched no memory was preserved of it. The Nation family appears to have moved on and continued to live their lives. (In contrast, Herman Husband fled the battle before it started and escaped to Maryland with a price on his head, where he lived under an alias until well after the Revolutionary War.)

Some historians regard the Regulator uprising as a precursor to the Revolution that was just a few years away. Others see it as entirely unrelated to it. The truth is probably found somewhere in between.

Despite Gov. Tryon's efforts to make the uprising an affront to the Crown, it was never about gaining independence from British rule. It was the essence of class warfare, an attempt by the poor and middle class to gain standing in a system dominated by the upper 5%, and who in utter frustration finally took up arms. While the westerners saw Tryon as an oppressor, the business and plantation interests of the east, deaf to their complaints, saw him as the upholder of proper order. He was well thought of and considered an able administrator when he departed later that year to govern New York. And when the movement for independence caught on, many of the prominent North Carolinian patriots looked with embarrassment on the Regulator revolution they had disdained and opposed.

Even so, the Regulator movement certainly embodied the growing tendency in the American colonies of people wanting to govern themselves and establish means to redress grievances. As news spread throughout the colonies of the Battle of Alamance, most of the public sympathy swayed toward the Regulators and many in the growing Patriot movement found inspiration in their resistance to unfair governance.

1 “Regulators,” Encyclopedia.com, op. cit. Italics mine.

5

The Passing of the Patriarch

The elder John Nation had entered his seventies by the time the Regulator movement had escalated almost to a rebellion. While we might suppose he was a sympathizer and supporter of the Regulators and his son, this was not his fight. We can only guess what infirmities his long life and toil and hardships had brought to him, but it is only natural that we would find him reducing his activity and slowing his pace.

1770 marked the fiftieth year of marriage for John and Bethiah. Did they celebrate? Did their children host a party for them? Not likely. Anniversaries or even birthdays were not a thing people celebrated in those days, least of all people who were raised by Quakers who celebrated no day above another other than keeping “Sabbath” on Sunday. Indeed, we only know John Nation's March 28 birth date—actually his baptism date—because the Church of England kept the record. Sentimentalism was not a feature of life for those who scraped out a living on the frontier.

In March 1772 the English-born, former servant-boy turned 75. By December of that year the old farmer realized that he had seen his last harvest. Summoning his family and some trusted neighbors he dictated a last will and testament that was written down by one of the men present, probably his son Joseph.1

Like his late brother-in-law and best friend Joseph Robins who died 18 years previous, he begins with a statement of his faith and calls on his heirs to bury him “in a Christian Like manner.” If his grave were ever marked, the marker is long since perished and the site of his last remains known only to God.

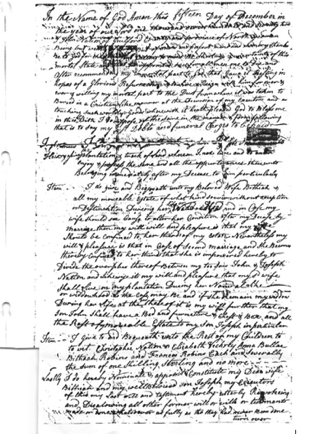

In the Name of God Amen--this fifteen day of December in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and seventy two, I John Nation, Senior of Guilford County and province of North yeoman, Being but weekly of Body, But of sound and perfect mind and memory, thanks be to God for the same, But calling to mind the shortness and uncertainty of this mortal State and that tis appointed once for all men one to die and after recommending my immortal part to God that gave it, resting in hopes of a glorious Resurrection & to live and reign with him for ever and ever, and willing my mortal part to the Dust from whence it was taken to buried in a Christian Like manner at the discretion of my Executors and as touching such worldly goods wherewith it hath pleased God to bless me in this life with, I do dispose of the same in the manner and form following, that is to say my just debts and funeral charges to be paid—

He bequeathed his real estate including the active plantation to his second son Joseph, indicating the property was already Joseph's home and that he was the current operator of the plantation. This would also make Joseph the caretaker for his widowed mother who would continue to dwell on the estate. Younger son John would receive, after his mother's passing, certain furniture items.

Item - I do give and bequest unto my son Joseph Nation, his heirs and assigns the plantation and track of land whereon I now live and to enter, enjoy and possess the same and all the appurtenances thereunto belonging immediately after my decease to him particularly.

Item - I do give and bequeath unto my Beloved Wife Bithiah & all my moveable estate of what kind soever without exception or distinction during her life or Widdow Hood, and in case my wife should see cause to alter her condition after my decease by marriage, then my will and pleasure is that my wife should be confined to her third of my estate. Nevertheless my will and pleasure is that in case of second marriage and she becomes thereby confined to her third, that she is empowered hereby to divide the overplus thereof between my two sons John and Joseph Nation and likewise it's my will and pleasure that my s[aid] wife shall live on my plantation during her natural life or widdowhood as the case may be and if she remain my widdow, during her life at the end thereof it is my will further that my son John shall have a bed and furniture and chest and box and all the rest of my moveable estate to my son Joseph in perticular. [sic]

Christopher and his four sisters were granted one shilling apiece.

Item - I give to and Bequeath unto the Rest of my children to wit: Christopher Nation and Elizabeth Vickery, anna Buller, Bithiah Robins and Frances Robins each and severally the sum of one shilling sterling and no more ----

Considering that this was his oldest son and that primogeniture was important in those days, does this mean that Christopher was shut out or under his father's displeasure? Not at all, for Christopher had already been given his share of the estate almost 20 years earlier. As we will see later, while he was not in the wealthy class, he had substantial holdings

Lastly - I do hereby nominate and appoint and constitute my Dear wife Bithiah and well beloved son Joseph my executors of this my last will and testiment [sic] hereby utterly revoking and disallowing all other former will or wills or testaments made or done whatsoever as fully as tho they had never been done.

It is significant also that John appointed Bethiah the primary executor of the will, in line with the Quaker tradition of equality rather than legal conventions of the time.

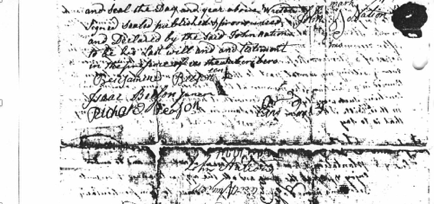

Rattifieing and confirming this and no other to be my Last Will and testiment, in witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal the day and year above written. [sic]

John Nation

Signed, sealed, published and pronounced and declared by the said John Nation to be his last will and testament in the presence of us, the subscribers.

Benjamin Beeson, Sen.

Isaac Beeson, Juneor [sic]

Richard Beeson.

Whether he survived another day is not known, but the date of the will (December 15, 1772) is regarded as that of his death. The will was in probate for one and a half years. As soon as it cleared, Joseph sold part of the property willed to him along with another plot he had received by “deed of gift,” a total of 235 acres. For it he received £270. The deed was signed by Joseph, his mother Bethiah (as “Bethyah”), and his wife Eleanor—once again demonstrating the Quaker values of equality.2

In May 1774, mere days after signing the deed, Bethiah Robins Nation joined her husband in death, and we presume was buried alongside him. We do not know that because their graves have been lost to time, but it only makes sense because they were inseparable in life.

What can be said about such a woman? She gave birth and raised eight children, even in the most primitive conditions. She made a home for her family in the wilderness while her husband cleared and broke ground to try to get a crop. Then, in middle age, she up and did it again three hundred miles away. Her role in nurturing and building this family cannot be overstated; yet almost all of our knowledge of this woman, apart from basic facts of her life, has to be inferred. Probably the most extraordinary thing about her is that, in her time, she was not extraordinary. Hundreds, even thousands of women did what she did, just as her husband did what hundreds and thousands of other men were also doing.

The passing of John and Bethiah Nation marks the end of a great American odyssey—not celebrated as the arrival of the Pilgrims but no less dramatic, and in its own way impactful on the history of a great nation. Known to family genealogists as “Servant Boy” from his identification in a will, he far surpassed his background as an orphaned immigrant and indentured servant, and together with his beloved helpmate carved out a country and build a community by faith and with his own hands. And, taking the ancient biblical mandate seriously, even literally, they went forth and multiplied and replenished the land with children who made their own contributions to building an America.

1 The will described here, found in Guilford County, NC Book A, page 277, file #0276, "Will of John Nation," was made December 15, 1772. The will was proved in court May 1774.

2 Guilford County, North Carolina, Deed Book One, p. 235, 18th May 1774, Joseph Nation of Surry to Willm. Borden of Carteret, five shillings Sterling, 235 acres, by virtue of his father's will & a deed of gift for 100 acres recorded in Guilford, part of the same tract, both the 100 acres & the other that fell to him by his father's will begin at a black oak on Hearman Cox's line, W 54 ch. to a black, S 39 to a black oak, E 20 ch. to a hicory, S to Joseph Lamb's line, E with Lamb's line to Cox's, N on Cox's line to beginning; Signed: Joseph (EN) Nation, Bethyah (B) Nation, Eleanor (E) Nation; Witness: Timothy Jessop, Willm. Jessop; Affirmed may 1774 Term by Timothy Jessop. P. 239, 19th May 1774, Joseph Nation of Surry to William Borden of Carteret, two hundred seventy pounds, 235 acres, this is release of lease recorded on page 235.

6

Days of Revolution

Considering the prominent role the Nations had in their community and in the Regulators conflict, it is natural to wonder how involved the family was in the American Revolution. Whatever their involvement may have been, very little made its way into historical record. Actually, in the wake of Christopher's controversial connection with the Regulators, that lowkey approach is quite understandable. All the pardoned Regulators had to take an oath of allegiance to the King, which put them under special jeopardy if the British found them to be “in rebellion.” Loyalists controlled the government until the Tory governor was taken prisoner in 1781. And to be sure, there was no love lost between the former Regulators and the Patriot leaders in North Carolina who had given no aid or comfort to the backcountry folk fighting for their rights a decade earlier.

That is not to say that the Nations were a Tory family. We know that Christopher's fifth son Joseph was a private in the Randolph County Regiment from 1779 to 1780.

From Carolana.com:

Quite a few North Carolinians were actively recruited by the Military units of other provinces and states…. Since so many of its men were already members of neighboring states' militia units or even enlisted as Continentals, the North Carolina Militia was usually a fairly poor fighting force. Poorly armed and poorly trained, the Militia generally received the least attention and the least funding. Many times, it was sent forward to fight - with no guns and only homemade broadswords, pikes, and axes.1

There must have been a powerful recruiting push at that time because Joseph, nearing 30, was a married man and a father. He had married Jereter Vickery on Christmas Day 1770 and at this time had one son, Sampson (b. 1775). He was not alone but had joined along with his cousins John and William Robins.

Serving in Brig. Gen. John Butler's cavalry brigade under Col. John Collier, 29-year-old Joseph was part of the army of Gen. Horatio Gates that was routed by Gen. Lord Cornwallis at Camden, South Carolina on August 16, 1780, one of the worst Patriot defeats of the war. According to his application for pension and bounty-land he served two enlistments for a total of nine months.2

Besides worrying about Joseph's wellbeing during his service, the Nations also had to be concerned with the threats of continuing Loyalist military activity such as by Col. David Fanning all the way through 1782. A number of raids and skirmishes took place in Randolph and the neighboring counties. The most significant battle took place in Guilford County some 10 miles north of the Nations' Polecat Creek property on March 15, 1781. It began, ironically enough, at a notable Quaker gathering place: New Garden Meeting House where Lt. Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee fended off the infamous Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton for the better part of the morning. The major battle, though, occurred further up the road at Guilford Court House when Lord Cornwallis's army encountered Gen. Nathaniel Greene's main force. Greene inflicted heavy casualties on Cornwallis before withdrawing, leaving Cornwallis in control of the field with a technical victory and a strategic loss.3 All the marching of armies and battlefield activities must have had an impact on the Nations.

The Revolutionary War had a clear impact, though, on the western regions of North Carolina—mainly growth. “In the early years of the war most of the fighting was in the northern colonies and many people from those affected areas chose to uproot their families and to move south, where life was still relatively peaceful. It is estimated that North Carolina actually increased its population by more than 100,000 people during the war.” The American Revolution in North Carolina: North Carolina Counties, 1775-1777.

This was the impetus for the creation of new counties with closer courts. Might the growth have influenced the life choices John and Bethiah's family made after the war?

1 Carolana.com, The American Revolution in North Carolina: All Known Engagements in North Carolina—Battles and Skirmishes. https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/nc_revolution_engagements.html

2 Ibid, The Patriots and Their Forces. https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/nc_patriot_military_privates_n.html

3 Ibid, The Battle of Guilford Court House. https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/nc_revolution_engagements.html

7

Christopher Nation's Last Days

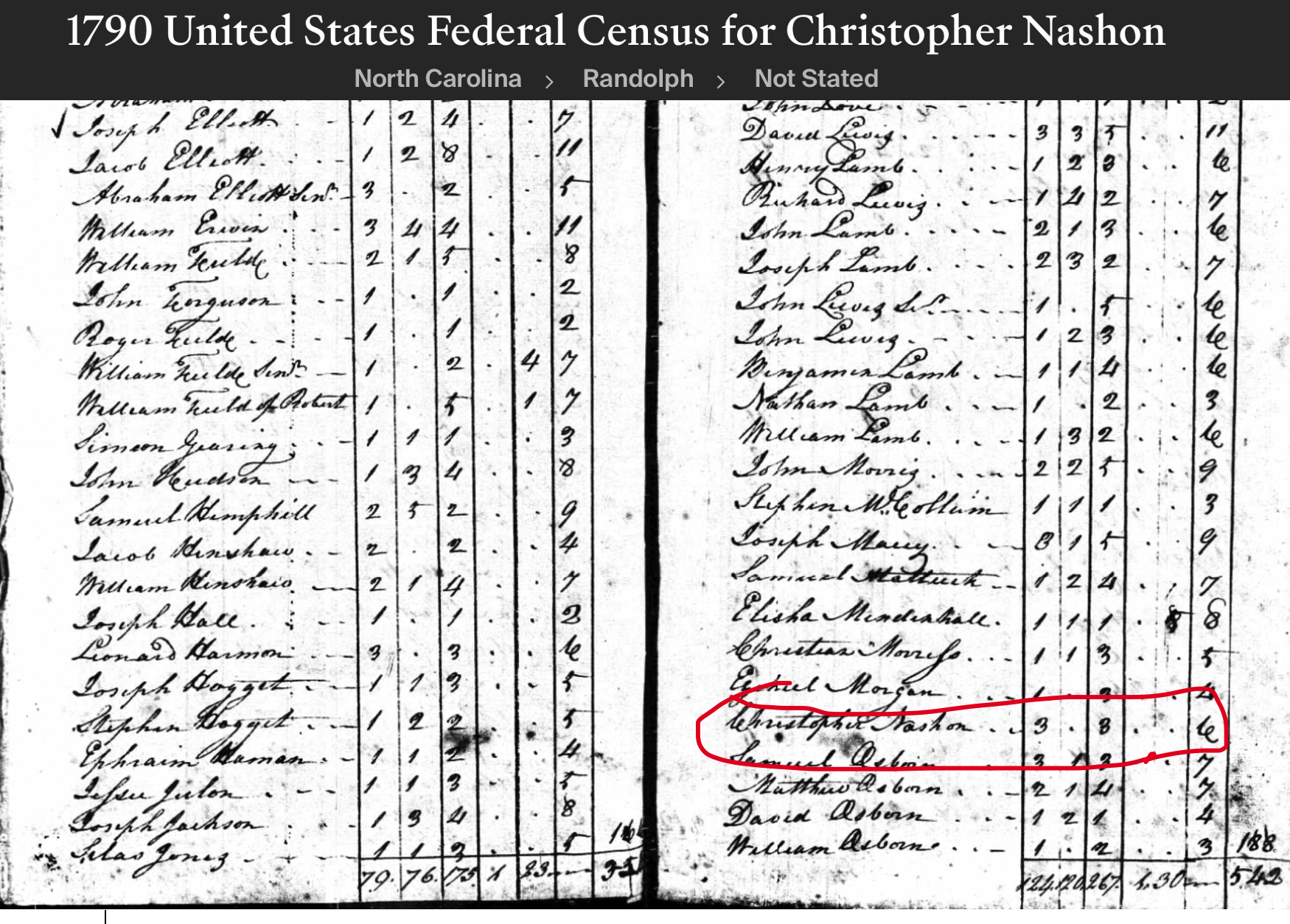

Christopher continued to trade in real estate. On August 18, 1787, Christopher Nation received a grant of 100 acres by the state of North Carolina. On December 20, 1791, he received another grant from the governor for 100 acres on Pole Cat and Deep Creek Rivers.1 He also continued to have a voice in community affairs. In 1788, he and his sons Christopher, Jr. and Amos signed a counter-petition to keep the Randolph County seat at “the Cross Roades” where “a good Court House Prison Pillory & Stocks have been lately Erected…in, and for the use of, the said County”; and that the assembly not be persuaded by “Some people” who “Seem to be dissatisfied therewith….”2

He had also suffered the loss of siblings. His brother John, four years younger than he, died in 1779. The death of his twin sister Anna Bullar in 1780 surely hit him hard. In 1787 his sisters Elizabeth Vickery and Frances Robins both died, possibly from the same illness. In all these seasons of bereavement he still had the comfort of his wife Elizabeth at his side.

In November 1799 he wrote a will.3 Like his father before him, he began with a declaration of faith.

In the Name of God, Amen! I, Chrisopher Nation of Randolph Co. and the state of North Carolina, being in a weak state of health, but of sound mind and good memory, thanks be to God! Calling to mind the Immortality of the body, and knowing that it is appointed unto man, once to die, do make and ordain this, my Last Will and Testament, that is to say, principally and first of all, I give and recommend my soul unto the Hands of God, that gave it; and my body I recommend to the earth, to be buried in a Christian manner, at the discretion of my executors, herein after named, nothing doubting but at the general resurrection, I shall receive again, by the mighty power that gave it….

Then he turned to the disposition of his estate. The details reveal a man who, though not wealthy, had experienced prosperity and desired to pass the benefits to his children, all of whom still lived either in Randolph County or neighboring Surry. It also reveals some interesting details about his children.

…and as touching such worldly estate as it hath pleased God to bless me with in This life. I give and devise and dispose of the same in the following manner:

He assigned the bulk of his estate to Abraham his eldest, but shows his namesake special consideration above his other children perhaps because of his leading role in the family business.

Item, I give unto my son, ABRAHAM NATION, 240 acres of land, including the buildings and improvements, to him, his heirs, forever, provided he shall pay or cause to be paid unto my son CHRISTOPHER NATION, or his heirs or assigns, the just sum of $100; but he case he should fail to pay the said money, the said CHRISTOPHER NATION, or his heirs, is to have just right and title to 100 acres of land, south of said buildings.

To his other children he gives the traditional shilling. But notice, his daughters, now in their late 40s, were unmarried.

Item, I give unto my five sons (Viz) JOHN, THOMAS, [JOSEPH], WILLIAM and AMOS NATION, one shilling apiece.

Item, I give, also, to my two daughters, ELIZABETH and BETHIAH NATION, the sum of one shilling apiece.

We do not know how long his wife Elizabeth Sharp Nation lived, but she was still with him at the end. And we see that the Nations still had close relations with the Vickerys with whom they had intermarried.

Item, I give unto my beloved wife ELIZABETH NATION all the rest of my moveable and personal estate, including the cash and cash notes, during her natural life, and at her disposal; and I also ordain and appoint my son ABRAHAM NATION and my friend CHRISTOPHER VICKERY to be my whole and sole executors, of this my Last Will and Testament. In witness whereof, I have set my hand and seal, this 11th day of January 1799.Witness present: ABSOLAM VICKERY.(signed) CHRISTOPHER NATION (Seal)Jurst J. Harper (copy), Nov term

The foregoing will was proven in open court by ABSOLAM VICKERY (abstract), land to sons Christopher Jr., John, Thomas, Joseph, William, Amos (one shilling each); daughter Elizabeth and Bethiah; wife Elizabeth; Executors: son Abraham and a friend Christopher Vickery. probated November term of 1799. Witnesses: Absolam Vickery and John Vickery

It would appear that the Nations were now firmly rooted in North Carolina and would surely be there for generations to come. But changes would come, and soon.

1 Microfilm F4895 pt. 1. Deeds of Randolph Co. N. C. Book III page 227.

2 Randolph County, NC, Petitions 1785 and 1788 Transcribed by Harold Hopkins.

3 Transciption of the Will of Christopher Nation from Ancestry.com.

Coming Soon:

The Settlers